Role of the Project Manager | By Leif Rogell | Read time minutes

Anyone who carries out routine work in a traditional organisational structure, e.g. paying salaries in a large company or manufacturing screws in a factory, can in principle work with more or less the same colleagues from training to retirement. During the process, you get to know them well, both the good and the less desirable sides and characteristics. Over the years, an order and team structure is established in the department and you learn how to deal with other colleagues individually.

New tasks are constantly being mastered in projects. Since different tasks require different competencies, the project organisation and the project team are newly assembled for each project to meet the upcoming challenges. This way of working together is becoming increasingly popular and can be observed in the form of, for example, matrix organisations.

If the working group, the project team, is constantly being reorganised, the probability increases that colleagues who do not know each other so well will have to work together. It is also true, of course, that the risk of misunderstandings and conflicts in such situations increases considerably.

Dealing with such 'superficial relationships' within a project team is part of the everyday work of a project manager. Those who understand the psychology of such situations can better assess the behaviour of their colleagues and, if necessary, steer them in the right direction. It is about what happens when people see each other for the first time, how people react differently to unfamiliar situations, how behavioural norms in project teams establish themselves very quickly, how a project team develops from a project group, how corporate culture influences project work, and how personal conflicts can quickly become disruptive factors in project work.

A successful project manager is expected to be able to deal with all these aspects of human behaviour, to take them into account in his or her project management and steer accordingly. Hence, a project manager must not only be well versed in project management methods, economic issues, economic goals and project organisation, but also in psychological aspects of human co-operation within the project environment.

Learning Styles in Project Teams

In projects, basically new and temporary tasks are mastered. Of course, if you are doing something for the first (and only) time, you cannot know in advance how to do it. This, of course, means that you have to teach yourself first (or along the way) how to perform the tasks. Therefore, there are great similarities between how to teach new skills or knowledge and how to approach a project task. For this reason, it is important for the project manager to know and understand how learning processes work and what different learning styles there are, as these can give hints and explanations for the behaviours in the project group. Some people approach new tasks by reflecting and observing, others prefer an active experimental approach.

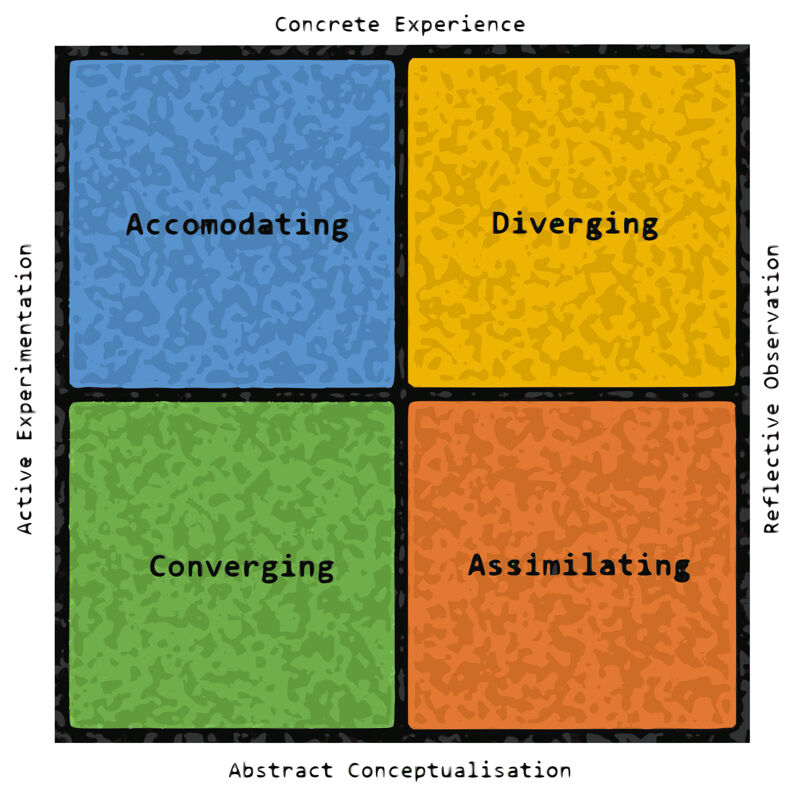

To describe the learning style Kolb uses two variables. The first variable deals with processes, for example, how we approach a new task. The two endpoints of this variable are 'active experimentation' and 'reflective observation'. The second variable deals with what we think about a new task and how we feel when we carry it out. The two endpoints here are 'concrete experience' and 'abstract concepts'. In Kolb's model it is assumed that we cannot deal with the two opposing terms at the same time, rather we must decide on one of the endpoints for each variable. Therefore, a matrix with four fields, each representing a learning style, is created from these two variables.

The first learning style is that of the discoverer (also called diverger). These people can look at new tasks from several different perspectives. They prefer to watch rather than try something out in practice. The second learning style is that of the thinker (also called assimilator). These individuals prefer a logical approach and prefer learning with ideas and theoretical concepts to interaction with people and teams. The third learning style is that of the decision maker (also called converger). These people tend to want to solve problems practically. They are more interested in technical specifications and functions than in people and groups. The fourth style of learning is that of the doer (also known as the accommodator). These people learn by putting different approaches directly into practice and trying them out, rather than thinking about the ideas and solutions in depth.

If you know the learning style of a project member, you will be able to better classify his or her behaviour when dealing with new, previously unknown tasks. In addition, the project manager can better support this person, as he can pass on new information and new knowledge in a way that best suits the learning style of the individual. Interesting in this context is that, some learning styles work better than other during different stages of the project life cycle. Imagination works brilliantly when working on the project scope, reflecting works well during planning and the hands-on-mentality is good for the project execution. A project manager aware of such phenomena can help the project team emphasise a helpful behaviour.

Phases of (Project) Team Development

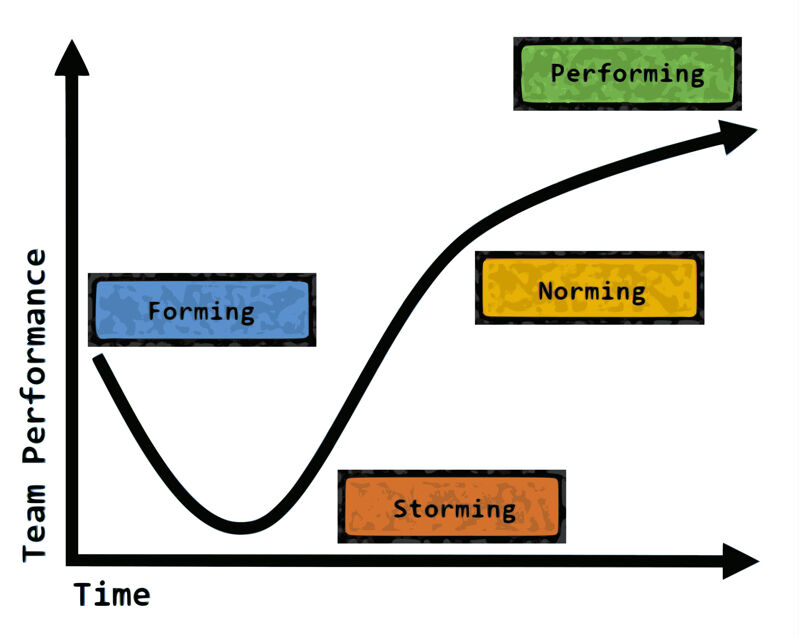

Teams, also project teams, do not start at their highest level of potential productivity. Once formed, a team moves through several phases that are characterised by different behaviours. One of the best-known models for team development is the Tuckman model. In this model, he describes four phases which every team must necessarily go through before a high-performance team is established. In this context, it is also important to remember that team development does not always follow this model strictly, since individual and complex human behaviour has a strong influence. It can therefore often be observed that a team sometimes jumps back and forth in the phases, that the phases partly overlap, and that some regression can also be expected. If new team members join the team or changes are made in the team, the team is reset to an earlier phase.

The first phase (forming) of a new team with new colleagues and tasks is usually exciting. Most team members are happy to have been selected for the team and hope to have a positive and enjoyable team experience. At the same time, they are worried about how they will be received in the team, how they will be accepted in the team, and if their performance will meet the requirements and team standards. At this stage, many questions are expected from the project team members, as they are still very uncertain about their own role. At the beginning, the questions are usually directed straight to the project manager, as they are still the natural contact person in this phase.

The second phase (storming): In the course of time and over the course of the project work, the initial uncertainty is gradually shed. The focus and attention of the project team members shifts from the actual activities and the question of belonging to the behaviour of the other project team members. The relationships with and expectations of the other members and their performance, moves to the centre of attention. Conflicts start to arise because project team members begin to express their opinions openly, introducing the risk of a clash of expectations. At this stage conflicts are also approached in an open fashion.

The third phase (norming): After (or if) the team has overcome the conflicts and a common understanding has been established, an atmosphere of satisfaction and belonging is created. The project team members can leave the conflicts behind and now have the common goal in mind. They no longer want to achieve the goal as individuals, but as a team. Normally the project team members now accept the different weaknesses and strengths of their co-workers and have developed an understanding of their roles and contributions.

Not all teams reach the high-performing phase (the fourth phase). To reach this stage, the team must have accepted all group norms and have established a balanced distribution of roles. Furthermore, all project team members must have accepted the behaviour of their co-workers and focus exclusively on the common goal. A constructive communication and feedback culture must have been established. If these conditions are met, the project team members are generally highly motivated and can work independently towards the common goal.

This team development model provides the project manager with additional information on the co-operation and interaction taking place within the group, the leadership behaviours can then be adapted accordingly throughout the different phases.

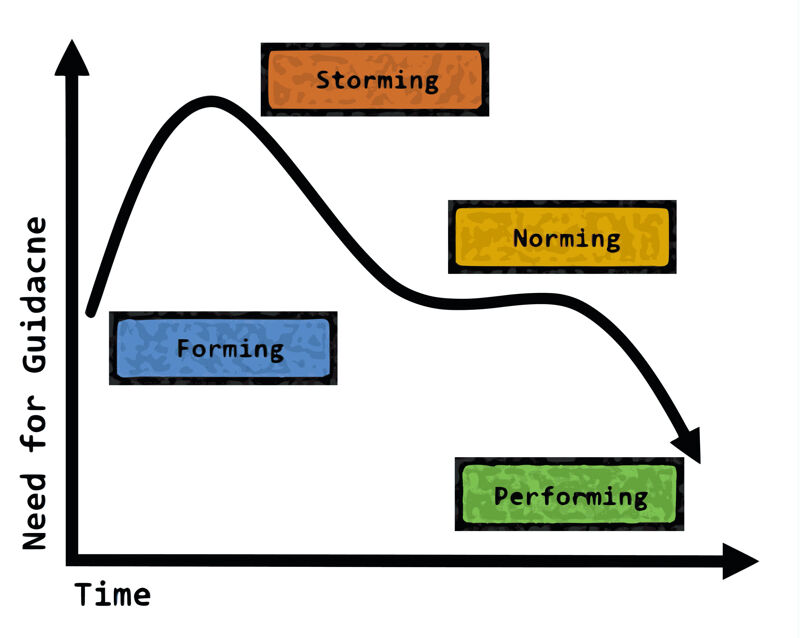

In the forming phase can be supported by the project manager by taking on the leadership role and setting the direction of the team. Tasks and expectations of the results and standards should be openly communicated. Open and direct resistance to the leadership style of the project manager is rare during this phase. The project manager can support the team by acting as chairperson and by structuring and organising the meetings.

The storming phase is generally more strenuous for the project manager, as they must justify their decisions, organisation and leadership methods to the project team members. The manager must control this slightly chaotic phase and at the same time listen to the project team members, in order to intervene in case of conflicts. Even if not all of the project team members' suggestions, ideas and change requests can be incorporated into the planning, the project manager gains confidence by showing the project team members that they are willing to listen. In this phase, it is often less important to explain the more precise goals and activities, but much more important to explain the way there.

As the team has accepted the common goal and is trying to work together to achieve it in the norming phase, the project manager can easily start to withdraw and to delegate certain responsibilities and activities. Since the project team members are no longer distracted by conflicts or relationships, they can start to tackle more complex tasks. In this phase, it is useful for the project manager to work on motivating the team as a whole, and as individuals. The project manager can also continue the work of involving the team more deeply in decision-making, longer-term planning and organisation.

In the performing phase, the team basically works independently and efficiently in all aspects towards the common goal, the project manager can stop focusing on the team. Now is the time when the project manager can turn their attention to the outside world. They should not only set goals for the team, but also share visions for what can be achieved in the future. These visions specifically concern the performance of the project team and are not regarding the project result. The project manager also acts as a pathfinder for the team by tackling external obstacles and clarifying organisational difficulties within the company, so that the team can focus on their activities, undisturbed.

Summary

Psychology (i.e. human behaviour) is present in the everyday life of a project manager. Unfortunately, this has not gained enough attention in project management education or literature. Learning styles and Tuckman's team development are two examples of psychological models that can help the project manager better understand his or her project team and how to improve interaction with the project team members.

One final piece of advice, when discussing psychology for project managers. As always when dealing with human behaviour, all I can do is to provide you with general ideas. But people do not always behave as predicted by psychologists. You can learn from these psychological models, but in the end, you need to be able to adapt those models and ideas in every encounter with your project team.

About the author

Leif Rogell is the owner and founder of bad project e.K. in Mannheim, Germany. He is the author of Psychological Project Management (available through Amazon).

Recommended read: The Five Stages of Team Development: A Case Study by Gina Abudi.