Do your Daily Scrums feel like a pointless ritual where everyone just lists what they’ve done yesterday, and what they do will do today? Does Sprint Planning feel like a waste of time because everyone only wants to know what they have to do? And does your Sprint Review consist of team members listing their individual accomplishments? If so, you are probably dealing with a complete lack of coherence and cohesion.

In our work with Scrum teams, we’ve been part of teams that had it. We’ve also been part of teams that didn’t. Some developed it over time. Others never did. In those cases where it never did, we now realize that there wasn’t even a team to begin it. And there was no compelling reason why there should be. So Scrum was doomed from the start.

This post is an exploration of scientific insights that help us understand what coherence and cohesion are, and why they are so important. We also explore how these insights create a strong foundation for the Scrum framework. We also translate scientific insights into practical applications, ready for use with your team.

This post is part of our “in-depth” series. Each post discusses scientific research that is relevant to our work with Scrum and Agile teams. With this series, we hope to contribute to more evidence-based conversations in our community and a stronger reliance on robust research over (only) personal opinions.

What are cohesion and coherence?

How does the Scrum Guide introduce cohesion and coherence? It defines Scrum teams as “a cohesive unit of professionals focused on one objective at a time, the Product Goal”. A bit further, it defines Sprint Goals as something that “creates coherence and focus, encouraging the Scrum team to work together rather than on separate initiatives”. So cohesion is described as a characteristic of the group, whereas coherence is described as a characteristic of the work that this group does.

Cohesion — or social cohesion, esprit de corps, commitment — has been studied extensively by social psychologists. A group is considered cohesive when its members are attracted by the idea of their group (Hogg, 1992). That is; the members like the idea of being part of their group and they self-identify as members of it. We see cohesive groups everywhere in life. From sports fans who unite behind their team to religious communities. And a group of friends, or a family, can also be more or less cohesive. But we obviously also find cohesive groups in the workplace. Organizational psychologists found that motivation is higher in cohesive groups (Beal et. al., 2003). They also tend to perform better (Evans & Dion, 2012), are better able to deal with stress and pressure (Salas, Driskell & Hughes, 1996). Wang et al (2006) studied software teams tasked with ERP implementations and found that cohesive teams performed significantly better than less-cohesive teams. High cohesion also comes with risks, such as groupthink and conformity to group opinions (McCauley, 1998).

“Cohesion — or social cohesion, esprit de corps, commitment — has been studied extensively by social psychologists.”

So what makes some groups more cohesive than others (e.g. Forsyth, 2009 or Brown, 2019)? The first factor is to what degree people like being part of their group, or are attracted to it. You may have seen this in your organization. Some teams in your organization may be well-known and highly regarded. These teams have a strong identity, and many people want to be part of it. The second factor is the sense of belonging that people feel and express as being part of that group. This is when people describe their other members as “family”. The third factor is the degree to which emotions are shared in a group. This happens when the members of a group celebrate successes together. But it is also apparent when members feel angry for being mistreated as a group. The fourth factor is coherence or coordination. This is when the members of a group actively coordinate their activities to achieve shared goals. This is when members check with each other about the next steps, enlist help from each other, and frequently communicate about their shared progress. In practice, we would call this “teamwork”.

This also makes coherence the most relevant to this post. It is what distinguishes a regular group of people from what we often call “teams” in the workplace. But not all groups in the workplace are actually teams, even when they are called as such. Teams require two characteristics to be met: 1) they require high cohesion of the group and 2) they have to strive towards coherence in the work that they do together. The first is a social characteristic of the group, the second a characteristic of their work.

“Teams require two characteristics to be met: 1) they require high cohesion of the group and 2) they have to strive towards coherence in the work that they do together.”

These insights illustrate nicely how the Scrum framework is grounded in learnings from social and organizational psychology, even though those foundations are not explicit. The Scrum Guide does talk about cohesion and coherence. There is a lot of sense to how the Scrum framework defines teams and how it encourages them to become more cohesive and coherent, as we’ll explore in more detail below. This recognition of the socio-dynamic processes in groups of people is also what attracts me to Scrum. It is also strangely absent in many other methodologies that are applied to teamwork. Even though I love a methodology like Kanban, I also struggle with its human-shaped hole. Many methodologies are so focused on process efficiency that they seem to ignore the human factors involved. Scrum feels different to me there.

“Many methodologies are so focused on process efficiency that they seem to ignore the human factors involved. Scrum feels different to me there.”

How Scrum encourages coherence and cohesion

In the previous section, we explored how groups are teams when their members gladly self-identify with being part of their team and when they actively coordinate their work to make it more coherent.

One of the challenges that many Scrum teams face is that they lack one or both of these characteristics — at least at the start. Often, Scrum teams are defined simply by putting a random group of people together. Although those groups can become very cohesive and coherent, it requires attention and purposeful effort to make that happen. Otherwise, they remain a set of individuals who work on their individual tasks and happen to be in the same room (or Slack channel). But this is not a team. And they will never become effective.

Cohesion makes people want to be part of a team and coherence allows them to work together towards shared goals. Fortunately, the Scrum framework offers four tactics that are grounded in scientific research.

Tactic 1: Shared Goals

The first is its emphasis on shared goals. Even though many Scrum teams still consider Sprint Goals and Product Goals as optional practices, they are in fact at the core of what makes teams more cohesive and their work more coherent. The value of collective goals has been long recognized in social psychology. Sherif (1954) demonstrated how collective goals make groups more cohesive, and can even reduce conflict. Specifically for Agile teams, Whitworth & Biddle (2007) found that commitment to team goals increases cohesion, team effectiveness, knowledge sharing, and feedback processes.

Tactic 2: Frequent opportunities to communicate

The second tactic to encourage cohesion and coherence is by providing teams with frequent opportunities to communicate. This happens during the various Scrum events, but also outside those events. A simple social reality is that familiarity and physical proximity breeds cohesion (e.g. Festinger, 1950). If members of a team meet frequently, they are far more likely to bond than when they don’t. Frequent interaction also creates many opportunities to find coherence in the work and to coordinate work in a team towards shared goals.

Tactic 3: Small teams

The Scrum framework recommends keeping teams small. Small groups tend to be more cohesive and coherent than larger groups. When everyone’s individual contribution is easily identifiable in the work that a team does, people are far more likely to commit themselves to shared work and feel satisfied by their contribution (Comer, 1995).

Tactic 4: Do it again, and again, and again …

As the previous tactics illustrate, cohesion and coherence develop over time as people work together. All teams start as groups of individuals. But many groups never become actual teams and never reach their potential. Fortunately, the iterative nature of the Scrum framework also gives you plenty of opportunities to encourage shared goals, frequent interaction, and redesign your team composition.

Don’t use Scrum when coherence doesn’t matter

Although many teams benefit from cohesion and coherence, there are situations where coherence isn’t important at all. This is the case when the members of a group really don’t need each other in order to successfully complete their tasks. This is relevant for many support departments, where members are simply required to handle tickets individually. But I’ve also seen this with groups of marketing professionals, consultants, and mechanical engineers. Similarly, I’ve also experienced one software team where every member was contractually responsible for a different product. Without any feasible means to change the work design of that team, Scrum felt wasteful to the group — and understandably so. This underscores how you should never use Scrum as a means to an end. It is highly effective in situations where teams benefit from coherence, but it is simply overhead where it isn’t.

4 tips to build more cohesive and coherent teams

So what if you’re faced with a “team” that doesn’t match these characteristics? For example, you may observe the following behaviors:

- Members don’t (want to) attend team events, like Sprint Retrospectives or Sprint Planning because they feel it isn’t relevant to them.

- Aside from the various Scrum events, there is very little to no interaction between team members during a Sprint.

- The team doesn’t have a name or anything else to give it an identity, other than people sitting in the same general vicinity (or in the same Slack channel).

- Members talk almost exclusively about “I” and “me”, and rarely about “we” and “us”.

In addition to the tactics already provided by the Scrum framework, I have found the following tactics ver helpful:

#1: Develop a strong team identity

A great way to create cohesive teams is by building a strong team identity. Our social nature means that we are inclined to join groups that we identify with. This ties into the sense of belonging and attraction that we discussed before as factors of group cohesion.

The simplest way to do this is by inviting teams to come up with a name, a slogan, and a Mascotte. Even such simple things already create a basic identity for the team. You can further strengthen the identity by referring to the team name, slogan, and Mascotte in various Scrum events. One of the teams I worked with picked a name similar to “Rubber Ducky”, and then rewarded itself with rubber duckies after a successful Sprints. Another team named itself “Bug Busters” and created a team poster with visuals that reinforced its team identity (see above). Even though such creative activities may seem odd in a professional workplace, they create a strong foundation for a team identity. I describe a more detailed approach in this post on how to kickstart great Scrum teams.

#2: Share positive emotions

Teams become more cohesive when they share positive emotions. Research with students, children, and workgroups shows that, on average, “success breeds cohesion, but failure lowers morale” (Brown & Pehrson, 2019). This explains why it is so helpful to celebrate successes, small and large, with your Scrum team.

“This explains why it is so helpful to celebrate successes, small and large, with your Scrum team.”

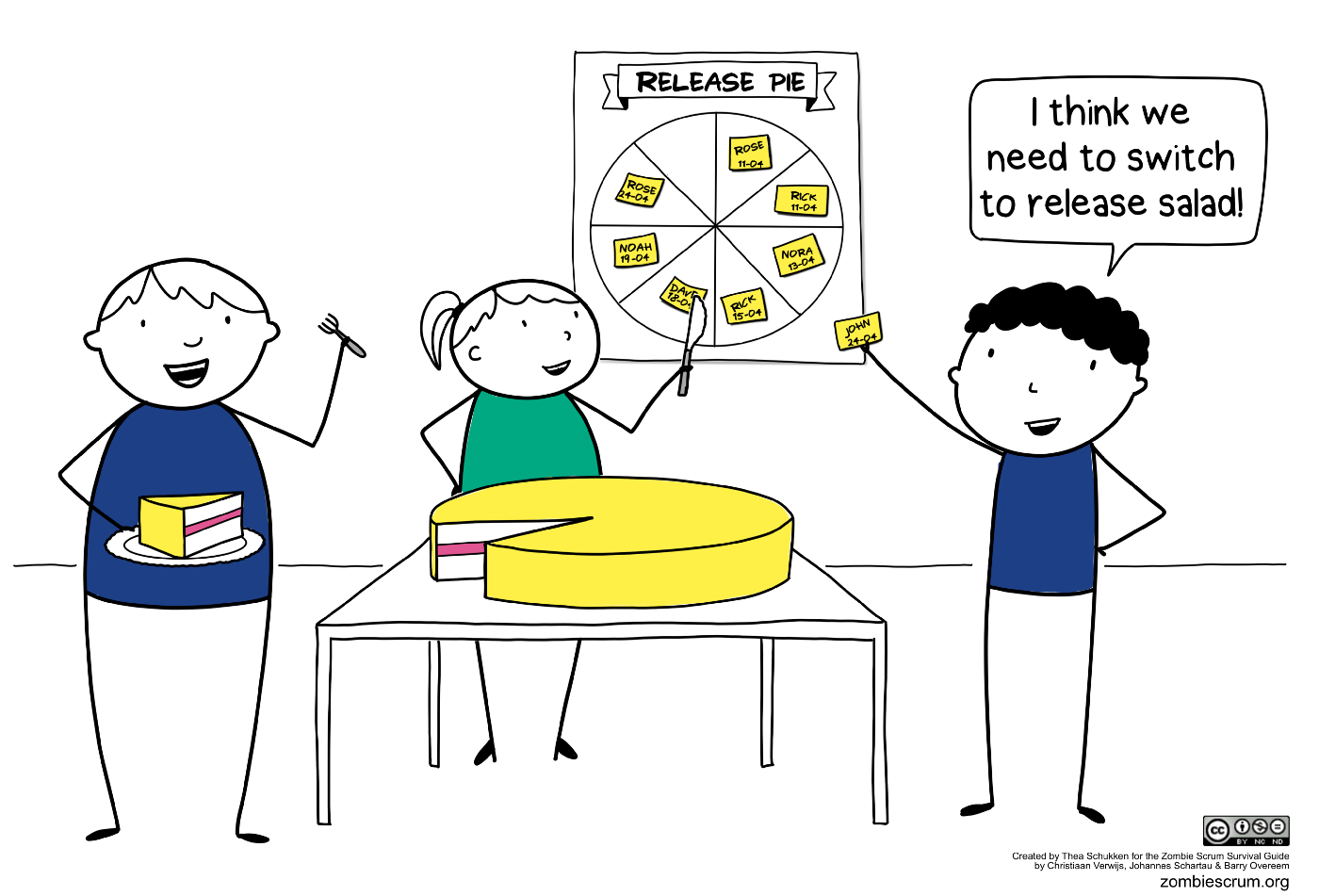

One way to do this is to celebrate each release. For example, we like to create “Release Pies” with teams. Every time someone deploys to production during a Sprint, one slice of the pie is filled. When the pie is full, we celebrate together with a treat. The point here is not so much what you celebrate precisely — a release, a satisfied customer, collaborated on a nasty bug — but that you celebrate it together.

#3: Work together, really

Where tips #1 and #2 are very helpful to create cohesion, they won’t improve coherence. That requires more deliberate coordination between team members towards some shared goal. The best advice here is to invest deeply in the identification of Sprint Goals and Product Goals. Because we know how hard this can be initially, we created three do-it-yourself workshops to help you here (1, 2, and 3). Each workshop is designed to help your team discover shared goals and coordinate their work accordingly to achieve those goals.

If all of that is still too hard, you can begin by encouraging members to pair up on tasks. By working on something together, people will start to see more opportunities to do so. At the same time, Product Owners play an important role here too. They can greatly encourage coherence by tying each Sprint to a business objective and by reiterating that purpose every time the team meets.

#4: Set the example

Finally, set the example by doing all the above — even if the team still feels awkward about it. You can add the team name to the calendar invites for Scrum events (“Daily Scrum for [team name]”). You can volunteer to pair up with others or invite others to pair with you. You can bring treats to celebrate a recent success. And you can use Sprint Planning and Daily Scrum to encourage members to work together rather than apart.

Closing words

In this post, we explored how many groups of individuals are not actually teams, even when we call them that on paper. Groups of individuals become actual teams when they are cohesive and when their work is coherent.

Cohesion is high when people want to be part of the team, and are proud of it, whereas coherence is high when members collaborate towards shared goals. Without coherence and cohesion, Scrum feels awkward and wasteful. And sometimes it's a sign that Scrum isn’t a good fit.

Many of the tactics and practices in the Scrum framework— like Sprint/Product Goals and its recurring events —are designed to encourage cohesion and coherence. And that turns groups of individuals into high-performing teams. This focus on the socio-dynamic nature of teams is also what makes Scrum so great to me.

I also offered four practical tips to encourage cohesion and coherence in your team. We offer many more do-it-yourself workshops in our webshop — many free, some for a small price.

References

Beal, D. J., Cohen, R. R., Burke, M. J., & McLendon, C. L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: a meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of applied psychology, 88(6), 989.

Brown, R., & Pehrson, S. (2019). Group processes: Dynamics within and between groups. John Wiley & Sons.

Comer, D. R. (1995). A model of social loafing in real work groups. Human relations, 48(6), 647–667.

Evans, C. R., & Dion, K. L. (2012). Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Group Research, 43(6), 690–701.

Festinger, L. (1950). Informal social communication. Psychological review, 57(5), 271.

Forsyth, D. R. (2009). Group Dynamics, 5th. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Hogg, M. A. (1996). Intragroup processes, group structure and social identity. Social groups and identities: Developing the legacy of Henri Tajfel, 65, 93.

McCauley, C. (1998). Group dynamics in Janis’s theory of groupthink: Backward and forward. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 73(2–3), 142–162.

Salas, E., Driskell, J. E., & Hughes, S. (1996). The study of stress and human performance. Stress and human performance(A 97–27090 06–53), Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1996, pp.1–45.

Sherif, M. (1954). Experimental study of positive and negative intergroup attitudes between experimentally produced groups: robbers cave study.

Wang, E. T., Ying, T. C., Jiang, J. J., & Klein, G. (2006). Group cohesion in organizational innovation: An empirical examination of ERP implementation. Information and Software Technology, 48(4), 235–244.

Whitworth, E., & Biddle, R. (2007, August). The social nature of agile teams. In Agile 2007 (AGILE 2007) (pp. 26–36). IEEE.