The podcast by project managers for project managers. How can agile project managers create conditions for self-organizing teams to thrive? In the agile world of a self-organizing team, the trend is to empower the team so the individuals doing the work can make decisions. So, what role do project managers play? Hear about the three responsibilities of the new agile leader and some important skills to level up in order to lead an agile project.

Table of Contents

03:03 … Humanizing Work

03:50 … Empowering Decision-Makers

05:21 … Changing the Role of Managers

08:20 … Challenges for Project Managers

09:32 … Complex Systems

11:33 … Defining the PM Role

13:58 … Coordinate and Collaborate

16:35 … Who Does It Well?

18:29 … What’s in a Title?

20:33 … The Three Jobs of Agile Management

23:49 … Project Manager Skills

27:25 … Visualization Skills

33:10 … Is Agile Right for Me?

36:39 … Contact Peter and Richard

38:19 … Closing

PETER GREEN: … one of the things that has been an underlying theme to these amplifier skills we’ve talked about – coaching, facilitation – is a real trust that the people doing the work can figure out how to solve it if I do the three jobs well. If I create clarity, if I increase capability, and if I improve the system for them, they will be able to knock this project out. They don’t need me to manage it…

WENDY GROUNDS: You’re listening to Manage This, the podcast by project managers for project managers. My name is Wendy Grounds, and with me in the studio are Bill Yates and our sound guy, Danny Brewer. We’re so excited that you’re joining us, and we want to say thank you to our listeners who reach out to us and leave comments on our website or on social media. We love hearing from you, and we always appreciate your positive ratings. You will also earn PDUs for listening to this podcast. Just listen up at the end, and we’ll give you instructions on how to claim your PDUs from PMI.

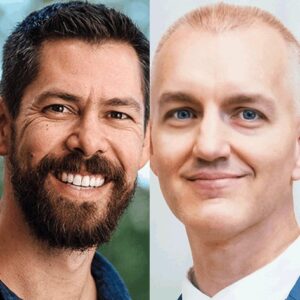

Our two guests today are from Colorado and from Arizona, so we’re kind of jumping around the place. But we’re very excited to have Richard Lawrence and Peter Green from Humanizing Work join us. Richard’s superpower is bringing together seemingly unrelated fields and ideas to create new possibilities. Richard draws on a diverse background in software development, engineering, anthropology, design, and political science. He’s a Scrum Alliance certified enterprise coach and a certified scrum trainer. His book “Behavior-Driven Development with Cucumber” was published in 2019.

Our other guest is Richard’s co-worker, Peter Green. At Adobe Systems, Peter led an agile transformation and he co-developed the certified agile leadership program from the Scrum Alliance. He’s also a certified scrum trainer, a graduate of the ORSC coaching system, a certified leadership agility and leadership circle coach, and the co-founder of Humanizing Work. What I found interesting was, with all his other creative activities, Peter is also an in-demand trumpet player and recording engineer.

BILL YATES: Which will appeal to Andy Crowe, our founder, because he loves to play the trumpet. Wendy, we are delighted to have Richard and Peter join us. We’ve had conversations planning for this today with them, and they bring so much knowledge and experience to the table. Here’s the thing. Project managers traditionally are taught to direct and control team members. So what role does management play in the agile world of a self-organizing team? If my team’s self-organizing, what am I supposed to do; right? How can they create conditions for self-organizing teams to thrive? What is the function of managers in this new world, and what does an agile organization need from its management team? Those are some of the questions that we want to tease out with them today.

WENDY GROUNDS: Hi, guys. Thank you so much for joining us.

RICHARD LAWRENCE: It’s great to be here.

Humanizing Work

WENDY GROUNDS: We first want to find out a little bit about you. So can you tell us about Humanizing Work and the company you say strives to help individuals thrive at work? So tell us a bit about your core philosophy.

RICHARD LAWRENCE: We believe at Humanizing Work that work can be a good and indeed important part of human thriving. So we see our work at our company as having two sides. First, helping organizations structure work so that it fits what’s true about humans. For example, that we have a need to grow, that we benefit from connections with others, that we particularly thrive when we’re creating things, and that we want our work to have an impact on other people. And second, helping humans develop the skills they need to do meaningful, complex work in collaboration with others.

Empowering Decision-Makers

WENDY GROUNDS: Thank you Richard. Traditionally, managers direct, and they oversee the work that their teams are doing. They’re the problem solvers and the decision makers and things like that. That’s what’s become expected of them. But the trend is to bring the decision maker closer to the team so the individuals doing the work can make decisions. How does that impact the role of the manager?

PETER GREEN: Well, I think to answer that question I’d start with why is that trend so really everywhere, omnipresent, right, in the business world. And what we found is that, kind of relating to what we talked about the purpose of the company, is that the more empowered people are in their work, the more we push decision making to the individual and team level, the better outcomes we get, number one. But part of that is that people are just more motivated. They’re more engaged when they feel like, “Hey, I have some input into this decision,” or “I can wholly own this decision.” We know from research on what leads to high engagement that the more autonomy people feel, the more they’re engaged in the work, and the better outcomes we get because of that.

And so I would start with that, that there’s a demonstrable reason for this, not just while it’s important to have people be more motivated and engaged, that helps with retention. That is just an ethical way to run a business; but that it also leads to better business results when we do that. We get better, faster decisions, and the engagement leads to good outcomes. So I would start there, like, why empower people?

Changing the Role of Managers

Then, if we agree that that’s a good idea, that we should do this more, then that really does start to shift the role of management from what you described as kind of doing the work, or telling people how to do the work, to something else.

And we struggled with this question ourselves as we managed in agile organizations that were really trying to empower the teams to do the work themselves, and as we helped lots and lots of managers try to face the same question. And originally we did not have great answers for them. I remember a very early training I was doing with a team, this would probably be in about 2008, and I was training this team in how to do agile things. They were trying to adopt scrum on this product team.

And I remember this. One of the managers on that team who was just really smart, really well-intentioned, still really admire this manager who came up to me on a break, I think somewhere towards the end of the second day. And he said, “I can see how this is going to be really powerful for the team. I can see how this is going to lead to really good outcomes. My title is senior engineering manager. I don’t have any idea what my job is now.”

And at the time I didn’t really have a great answer for Chris, this manager, when he said, “So what do I do?” And I felt like the answers that I had read about or that I had tried out sort of fell into three categories. One category of answer was very fuzzy. “Like, well, Chris, now you’re a servant leader.” Well, what does that mean? I kind of like the philosophy, but what does it mean to be a servant leader? It’s not very tactical, or I can’t put my fingers on it; right? Like what do I actually do to be a servant leader?

There were some answers that just felt demonstrably wrong to us. Like, oh, if we empower our teams, then we don’t really need managers anymore. And we had just seen the opposite be true in really successful organizations that had really effective management. And so while it is true that there are some organizations that are really interesting case studies of what happens if you don’t have managers – in fact, Richard and I met because he had helped an organization transform to where they had completely removed the management layers.

That’s what attracted me. Hey, let me talk to this Richard guy and see what he has going on over there. But that didn’t seem to be broadly applicable in every situation. So we thought, well, that’s probably not the only answer, and probably not the answer for most companies.

And then the third kind of answer that we heard was just incomplete. Like we often heard advice like, well, managers just remove impediments to the team. We said, well, that’s probably true, but that also feels like a pretty narrow job.

So we started looking for how do we answer that question? I always think if Chris were to ask me that question today, what would I tell him? And the very cool thing is that we have kind of evolved in cooperation and collaboration with a ton of different organizations out there, a model for that. And what we’ve boiled it down to is that managers really have three jobs in an organization if they want to empower their people.

Challenges for Project Managers

BILL YATES: This is right where we want to head. But I want to step back for a second and kind of take a 35,000-foot view at the role of a project manager before we go deep into some of this advice for those that are trying to figure out my world now with traditional versus adaptive and looking at that. But first, looking at the role of project manager today, I mean, it’s evolving. It’s changing. What do you guys see as some of the biggest challenges to project managers today?

PETER GREEN: I think one way that I would answer that question is to look at kind of two categories of work. There is some work that we need to manage that is pretty linear and predictable. Right? What system scientists would call “ordered systems.” Ordered systems is where I can do some analysis. And, based on the analysis I can lay out a schedule, I can map that out, I can map a whole project out. I can predict the results. And I won’t be wrong.

And a lot of the physical scientists, you know, I think largely manufacturing falls into this. So if I’m a project manager who is primarily responsible for getting manufacturing processes to be repeatable and predictable, that would fall on the ordered side of this.

Complex Systems

The other category, though, is where the outcomes are not predictable. What, again, system scientists would call “unordered systems,” what we would call “complex.” And complex really just means that you can’t predict just through analysis what’s going to happen. So product development is this way. Product development is complex because we can’t just go ask our customers or our users or our stakeholders “What should we build?”, do really good analysis of what they tell us, and then know that we’re going to build the right thing because there are just too many interdependencies there. People are really bad. By people I mean all of us are really bad at predicting our own behavior; right? Hence why we all sign up for gym memberships in January, and then by February 18th half of it has fallen off.

BILL YATES: Done that.

PETER GREEN: Right. So we’re not good at predicting our own behavior. And in a complex system like product development, the only way to learn what to do is to start doing it and to get feedback on it. And so I think one of the ways that we answer this question of how has project management changed is that more and more of project management falls into that unordered side, into that complex side.

If I’m managing a complex effort where I can’t really plan everything out, then the job of project manager gets much more difficult compared to how we traditionally define project management, where I’m gathering requirements, I’m doing analysis, I’m creating a project plan, I’m looking at resources and budgeting for that, I’m mapping out a schedule. And then I’m following up on the schedule to make sure that the project’s going to come in on time, on scope, on budget; right? Kind of really traditional project management definitions. If the work is complex, what do I do now? Because I can’t do that at the beginning of the project.

So the biggest challenge we’ve seen for project managers is how do I manage complex work? Because just traditional planning and follow-up and status reporting and all the things that really good project managers do well, that does not work anymore if the work is complex.

Defining the PM Role

RICHARD LAWRENCE: I was just going to highlight another challenge specifically related to the agile world. I think another challenge that project managers are experiencing right now is that the role has become less clearly defined. You know, it’s already a title that means a lot of different things in a lot of different contexts.

Most of our clients who are using something like scrum don’t have anyone with the title Project Manager, though they have a lot of people who may have previously had that title and are now doing something else. And if you list out all the things that a project manager used to do in those organizations, you discover that those responsibilities, many of them end up distributed across product owner, scrum master, and developer roles in scrum terms. So now what was my job is now maybe partly my job and several other people’s jobs.

There’s an exercise we do with clients sometimes where we actually list out all the things project managers have done and then make five columns. Product owner does it now. Scrum master does it now. Developers do it now. We don’t need it anymore. Or we need it, but we don’t know who does it. And then we’ll go through and try to figure out where each of those things go. And in a lot of places, if it’s highly complex, single team building a product, a lot of those things do end up in the scrum roles.

But then as it gets bigger, or there’s a mix of complex and this more ordered, complicated stuff, you end up with things in that last column. We still need to do it, but we don’t know where it goes. Like we’re doing product development for something that’ll go to manufacturing. Who talks with the manufacturing people downstream? That doesn’t fit nicely into our scrum process. Who talks with the regulators?

And so there’s all these other things around the edges of product development. And those are the places where we actually have seen clients realize we need another role here that works with all these other roles to be responsible for all these things outside and downstream of our team, coordinating often with other groups or teams.

BILL YATES: This is a big challenge. I’m really glad you guys brought those two things up. And it leads me into this follow-up question of, I know you guys have researched and worked with organizations that have done this well, where they figured out, okay, now we’re using agile. We’re getting more experienced with it. We’re even feeling like we’re getting successful with it. But who’s managing what? So if you could describe a couple of examples of organizations that seem to be figuring out that role well? Who’s leading or managing in these agile teams?

Coordinate and Collaborate

PETER GREEN: I want to give one other distinction here that I think helps answer this question. When we’re working on something that’s complex, we need a different style of interaction than if something is ordered. On the ordered side, since you can plan it upfront. We can plan together, and then people can go off and execute their separate parts. Because we know that the parts will come together and integrate and form the whole. That’ll work, if the work is ordered. And so we’ve come to call that style of interaction “coordination.”

Now, I know that coordination means a lot of things in a lot of different contexts. For us, coordinate, “ordinate” essentially means put in order or plan together; right? So when the work is ordered, we can coordinate, and then people can execute separately. Then, if we look at when the work is complex, in other words, things are going to emerge. Our understanding of what to build, how to build it, how to work together is going to emerge while we work on the project. We need a different style of interaction for that type of work. And so we really need to do the work together. In other words, co-labor or collaborate.

And so we’ve started making a distinction between coordination and collaboration. And collaboration works in teams because, if we say we’re going to either do the work together or be available to respond as soon as something emerges, we can create working agreements within a team boundary to say, “Hey, Richard, you and I are working on something on the same team. I’m going to start going down this path with this part of it.

But if I learn anything, or if I get stuck on anything because something surprised me, I need you to be available so that you can either give me feedback on what I’ve done so far, or you can help me get unstuck on the thing.” And that works pretty well within a team boundary.

And so our biggest advice when we’re looking at how we structure an organization is to say we need to locate core complexity within a team boundary because it’s really difficult to coordinate across teams if something’s emerging. Teams just have – they have a style of working. They come up with communication protocols. They come up with ways to collaborate effectively that don’t work very well when you span that across teams.

So that distinction between locate core complexity within a team where we can collaborate as things emerge, versus we can plan this and coordinate it, and then we don’t need the same type of communication style or protocol outside of teams is where I would start with this. So back to the original question now of…

Who Does It Well?

BILL YATES: Who does it well, and what can we learn; right?

PETER GREEN: Who does it well; right? And so the organizations that are doing this particularly well have done that first pass of what are the core complexities that we need to handle in our business, and how do we build teams around the core complexity? In anything larger than maybe a 15, 20-person team, the teams across the organization still need some information sharing. They still need to coordinate the pieces that are not complex across the teams.

And so that’s where we find the role of project management coming back in, in those organizations that are doing it really well, is that within the team, we don’t need a lot of project management. As Richard described, the project management role kind of gets broken up between kind of scrum roles, product ownership, deciding what to build in what order, scrum master, facilitating all the stuff happening in the team, developers really doing the work and keeping track of their own progress and that kind of thing.

The project managers that are doing this in organizations like this are really focused on cross-team things, cross-team coordination, not collaboration. Again, we use those to mean two very different things in our way of seeing this. So those organizations are doing it that way. They’re saying the project manager’s job is to coordinate across teams. And sometimes that’s a project manager, and sometimes there are other structures that people use for that. But it really is a coordination effort across teams.

RICHARD LAWRENCE: Along those lines, if you as a project manager are finding yourself managing sort of the work itself, and getting into the details, and having to run between teams to share information about something that emerged and adjust their plans with them, that’s a signal we probably have the wrong structure, that we’ve got complexity spanning teams, and we’re trying to manage our way out of this instead of doing the structural fix and then allowing people to collaborate around that in the same team.

What’s in a Title?

BILL YATES: I personally have never been big on titles, but this intrigues me a bit because now we go, there are so many titles out there for this new agile leader. It’s sort of laughable with our instructor team. We talk about, “Hey, what did you hear this week from the team that you just worked with and trained?” You know, agile coach, agile mentor, project leader, project manager, agile project manager. Have you guys found any consistency with the titles that are out there? Or is that still kind of specific to the organization?

PETER GREEN: I think the biggest consistency we found is, A, inconsistency; and, B, using titles that don’t actually match what the person is doing at all. You mentioned the agile coach. Like we have a pretty distinct way of saying what is coaching? What does it mean to coach somebody? And we see agile coaches that are being asked to do everything but coach. So they have that job title. There’s not a lot of coaching going on. It’s like, “Your job is to install the agile.” It’s like, “Well, hey, that’s not how it works.”

BILL YATES: Go do it, coach.

PETER GREEN: But, yeah. Other than that, we haven’t seen really good titles that are consistently used. And I’m not too worried about that. I used to always have this joke when people would say, “Well, what does a project manager do?” Which is to say, “Well, the thing that you call a project manager in your company is 180 degrees different than this other company I worked with last week.” So we can’t agree on even what that word means.

We might as well come up with a title that matches what you’re actually doing. It does make it difficult when we’re trying to talk to the world of project managers, and we’re trying to have community around what does good project management look like. It does make it difficult. We tend to just go with the industry norms there and say, hey, we want to talk to a bunch of project managers. Let’s get on the Manage This podcast and talk to project managers.

BILL YATES: Awesome.

PETER GREEN: Knowing that that means we’re talking to people that are doing a wide range of actual jobs.

The Three Jobs of Agile Management

WENDY GROUNDS: I think that ties us back to what you were talking about earlier. The three jobs of agile management. Can you define them for us?

RICHARD LAWRENCE: Sure. So we were trying to figure out how to give a good and useful answer to people with “manager” in their title for what do I do now if people are empowered? I’m not directing their work anymore. I’m not kind of managing their work day to day. What is my job? We started looking at places where that’s done well. What are they actually doing? And we found it was essentially three jobs.

First, create clarity, like help people understand what the work is, what success is, where are we going, what’s our strategy, that kind of thing. Increased capability, which includes things like technical skills, but also includes interpersonal skills. And it’s not just individual competence, but it’s also things like hiring and getting budgets. So making sure we have what we need to actually do the thing we’re trying to do. That’s increase capability. And then the third job is improve the system, all those different things that help the work flow smoothly.

That can be from, again, a human side of things like creating psychological safety, all the way to very practical objective things like what are our workflows and processes, and how does information flow, things like that. So create clarity, increase capability, improve the system. And then we’ve identified a number of focus areas under each of those that you can spend time on, even think about as a dashboard as a manager. Which ones am I responsible for? What state are they in today? What do I need to do to move those forward?

BILL YATES: That’s really helpful. And I’ve seen the model that you guys have on your website. It’s really helpful to look at that and see those subcomponents. You know, Richard, to your point, then it’s like when I read, for instance, “increased capability,” and then I look at some of the subpoints under that, it really resonates with me. A dashboard’s a great way to describe it. I can kind of self-rate or have my team rate me in those areas and say, “Okay, where am I doing okay right now, but where am I in the yellow, or maybe in the orange, and I need to pick it up?”

RICHARD LAWRENCE: In fact, just today we were working with a couple middle managers in fairly large organizations, one from an insurance company, one from a bank, and talking with them about their job. And one of the activities we did was pulling up that detailed “three jobs of management model” with all the focus areas, and we gave them some icons to move around, including drop these where your direct reports wish you could spend more time. Drop these where you wish you could spend more time. Drop this one where there’d be the highest leverage for what you influence, and use that model as a way to think about where should I be spending my time to have more of an impact as a manager?

And we also talked about what are some things you get for free, maybe because someone else does it, like I get a strategy from more senior management. My job isn’t making strategies, just communicating it. Or I work in an area where people come in with a lot of technical skills, like a friend of mine is an executive at a hospital. He doesn’t really need to worry about the medical skills of the doctors and nurses who report to him. He’s much more concerned about improving the system in which they work because he kind of gets skill and purpose from the industry for free.

Project Manager Skills

WENDY GROUNDS: So if they’re not really needing the technical skills, what are some good skills that a project manager should have?

PETER GREEN: So as we’ve identified this three jobs model, what we recognized is that there are amplifier skills around all of them. A good example of that, and one that comes up frequently, and that we’ve already mentioned, is coaching. Like what does it actually mean to coach somebody?

And the core stance when we’re going into a coaching approach is that we believe that the person I’m coaching is fully intelligent and creative and has what they need to solve this problem on their own without me giving them advice. My job is to help them explore options to uncover things that maybe are hidden from them or that they aren’t seeing clearly, but not because I pointed it out, but to ask them good questions.

I’ll give you an example of one that came up today where somebody asked a coaching question. We were practicing coaching questions, and somebody asked a question like, what other resources or allies could you enroll in helping you solve this problem? So that’s an open-ended question that we don’t know the answer to as a coach. And that person said, huh, I’ve never considered that this wasn’t just my problem to solve. Let me think about that for a minute.

That’s how you know you’re on the right track as a coach, when somebody says, “Huh, that’s a good question. I don’t – hmm. Let me think about that.” That’s what a great coach does is ask questions, reflect something back that causes the person to think more deeply about it or think differently about it than they were before.

And the great thing about that is that, even if the person coaching already kind of knew what that person should do or had a good idea that they probably ought to go down this path, and they probably ought to reach out to Joe over here in HR because they could help you solve that problem, because they asked what other resources or allies could you enroll, now the person came up with the answer. So they’re much more engaged in executing on that. And they feel like they’re the ones that did it.

Like I didn’t just go to my boss and or the manager, and they just told me what to do. I came up with this on my own. And next time I’m facing this, I might remember that question. And so you’re increasing the capability of the people by just asking questions, doing some of the other core coaching skills that we teach.

RICHARD LAWRENCE: Another skill that is useful for a lot of these different ones on here is facilitation, which is helping a group make a better decision than they would otherwise make without you. And I think a place where that particularly connects with a project manager’s expertise, if they go into this kind of model for their work, is the Workflow Focus Area under Improve the System.

That’s one where you might be tempted to go lock yourself in your office and design the perfect workflow for a team that is struggling with their workflow. Yeah, I’m going to go improve the system for them. But you could pull out that facilitation skill and say, why don’t I get the people who are closest to the work in a room together, or on a call together, and let me facilitate a focus conversation with them to improve their workflow.

And this often happens in something like scrum in the context of a retrospective, but it can happen all over the place. When you have a group that has collectively more information about the problem than you do as a manager, that facilitation skill is a way to draw that out of a group and help them reflect on it together and make a better decision than they otherwise would. So that layers onto this model. And you can take any of the focus areas and say, how might I use coaching or facilitation or a number of other things to help amplify what can happen in that focus area.

Visualization Skills

PETER GREEN: I can think of one other really valuable skill that most project managers have, which is visualizing things. How do you make it visible? And even in the example Richard gave of facilitating a conversation about workflow, visualizing the way things are today, how do decisions get made? How does work flow from one part of the system to another? Creating a good visualization of that is something that most project managers do every day, is figure out how to visualize things.

And we’ve seen the best change agents that we’ve ever worked with are particularly good at visualizing the thing in a way that somebody that could influence change in that area can look at the visual and immediately know what they need to change. We’ve seen this shift a team or an individual’s perspective from, ah, it’s just the way things are, there’s nothing we can do about it, to huh, I could actually influence things here if I could visualize this the right way.

I can tell you a story about that. I was once working with a product owner, and this was a product owner who was in charge of getting pricing and promotions updated on a company’s website. And this product owner had four teams that were pretty functionally structured.

So there was a team that did SAP backend work, updating SKUs in SAP, that kind of thing; another team that owned the backend of that website, the nuts and bolts guts of the system; a third team that owned the front end of that website, like how do we actually get this into the user interface? Then a fourth team that did testing.

And she had gone through some training with us, and we recommended that there’s probably core complexities spanning those four teams. And we might be better off creating a cross functional team so that we could locate the complexity within that team boundary. She said, “That’s a great idea. I’m going to go propose this to my vice president, that we restructure the teams this way.” And the vice president’s response was something like, well, we just did a reorg last month. I don’t think there’s a lot of appetite for another reorg so soon. We can’t do it right now.

And so this product owner said, I don’t think this VP gets how bad this is. So she sat down with each one of those teams. And she said, when somebody comes to you with a request for a promotion – hey, we need to put this thing on sale because our numbers are a little bit low this week or this quarter – what happens next, and how long does it take? She did this beautiful Visio diagram. And I say “beautiful” a bit ironically because it was not beautiful. It was messy. It was complicated.

BILL YATES: It showed the problem.

PETER GREEN: There were all these branching decision trees. And it visualized how messy it was to actually get an idea in this VP’s head because often these requests were coming from that VP. All the way through to it’s live on the website, and it’s working. The next thing she did was to do a little bit of cycle time measurement on each of those. The SAP team cycle time, average cycle time from a request to it’s ready in SAP. Same thing with each of those teams. And then do a value stream map on that to say, where are we waiting? Where are we actually adding value?

So she mapped all of that stuff out. And then she asked a couple of people from each team to just say, let’s imagine for a minute that we had a cross-functional team, and we had a request like this come in. How might it work if we were a cross-functional team? What might the cycle time go down to?

One of the things that she uncovered in that process is that there was a tremendous amount of rework. Where, when it finally got to the testing team, they would say, hey, this one looks like it’s supposed to only be in the U.S., but this promotion is going live to every geography. Is that right? And they would go back and they would say, “Oh, no, U.S. only.” They’d have to start over. She found that about 50% of it was rework.

So her next presentation to that vice president was the messy Visio diagram to say, this is how things get done right now. The current statistics on that, which is it takes about two months on average for any requests to get all the way through this system. And about 50% of them require rework. And a potential future state where it was like a single scrum team that was cross-functional.

They predicted that they could get two or three pricing promotions through in a two-week sprint. So average cycle time going down to a number of days instead of two months. And that rework would go next to nothing escaping a sprint. She said, “So my proposal is that we increase or we decrease our cycle time from two months to five days. We decrease rework from 50% to less than 5%. And all that it would take is this cross-functional team, VP. What do you think?” And the VP said, “Why haven’t we done this already?”

BILL YATES: Oh, that’s fantastic. Kudos to her for that communication, the analytical skill and know-how and the ability to then get the right information from the different teams and present that that way. That’s a great example. What I love about these examples that you guys have given for these amplifier skills is they apply across the board. Whether I’m leading an agile team or a more traditional team, these are fantastic areas for growth for me. The better I can be at facilitating, the better I can be at running effective meetings.

Then I suddenly have team members that want to work with me on future projects. It’s like, hey, you know, Bill doesn’t waste time. He gets in there, and he hears every voice. He makes sure that everyone gets to contribute. And we come up with what we think is the best plan. I want to be on his team next time. These amplifier skills pay off, not just in terms of that current project, but in terms of that individual and the organization just taking it to the next level in terms of maturity.

Is Agile Right for Me?

WENDY GROUNDS: We did a podcast, Episode 66, “Is Agile Right for Me? We had Steve Kraus, and that was quite a long time ago. And he was saying it’s good to take a step back and say, well, is agile the right thing for me? Or should I just be doing more traditional project management? Can everyone make the transition? What are you seeing? Are some people saying this is not for me?

PETER GREEN: I would answer that question in two different ways. Is agile right for me? The first way I would ask that question is, is agile right for this project? And we would use the same two types of work, the two broad categories of work. Is the work ordered, predictable? Agile’s not going to give you a ton of benefit there. There’s going to be some human benefit there. There’s going to be some transparency on even an ordered project that might come from adopting a lot of practices from the agile space.

But the real reason agile emerged in the world is to address complex things where you really couldn’t plan it out. You needed to take an emergent, iterative approach to it.

So that would be the first thing I would ask is that, is agile the right thing for this project? If the answer is yes, there is some complexity to this. There is some uncertainty to this, as we’ve done these projects in the past, we’re often surprised. Or shortly before the project deadline, things blow up. The status report that was green suddenly goes red. Those are all indicators that there probably was complexity hiding in those types of projects in the past, and we might benefit from an agile approach.

So if the answer is yes, then the question is, am I the right person to manage that project? And to answer that question I think requires some introspection. Because one of the things that has been an underlying theme to these amplifier skills we’ve talked about – coaching, facilitation – is a real trust that the people doing the work can figure out how to solve it if I do the three jobs well.

If I create clarity, if I increase capability, and if I improve the system for them, they will be able to knock this project out. They don’t need me to manage it in a traditional way where I’m asking for frequent status, where I’m creating the tool set for them versus facilitating those conversations for which tools should we use for this thing, right, where I’m really empowering the team.

So the first thing that somebody really needs to answer for themselves is, do I trust this team? If I don’t trust the team, I’m not going to be an effective manager for them. Then there is really the skill building part of it. And say, okay, I do trust them, but I’ve never done it this way before. I don’t really know what I’m supposed to do now.

And that’s really where starting to dive in and let me go get some coach training. Let me go take a course on facilitation or read our favorite book on facilitation. Which is “The Art of Focused Conversation.” Let me read “The Art of Focused Conversation” and dig into that model and figure out how I can be a more effective facilitator.

Let me go get some books on visualization and figure out how I can visualize the system. All these things we talked about, we’ve got a whole book list for each of the focus areas in the three jobs. Let me pick the one that this group or this team is most likely to need from me. Read through that book; make sure that I’m testing those things out. And just think of it like it’s time for me to skill up here. It’s time for me to level up my skills. What do I need to level up in order to lead an agile project the way that an agile project should be led? Just empower my team, and I’ll do the three jobs.

Contact Peter and Richard

WENDY GROUNDS: If our audience wants to find out some more about the work that you guys do, I know you guys do a lot of training, as well. How can they find out more about what you guys do?

RICHARD LAWRENCE: You can find more about what we’re doing and links to all of our social media profiles, to the Humanizing Work show, all the other things we’re doing online at HumanizingWork.com. That’s kind of the center of where you can find us online.

PETER GREEN: And I will emphasize the show, which is we do have a weekly podcast and YouTube channel. About half of those are people ask us questions, what we call our “mailbag episodes,” where somebody’s got a challenge, and we work through how we would think about that challenge. So in addition, you can find that on the website, as well. But you’re welcome to search YouTube or any of your favorite podcast sources for the Humanizing Work show.

WENDY GROUNDS: Yeah, I’ve listened to your show. It’s great.

BILL YATES: Yeah, great resource. And you alluded to the book list that you guys have for the different skill sets. That’s so helpful. It’s funny because I naturally build that into presentations or courses that I have a hand in writing. I just think, you know, okay, there’s a tiny little bit of information in my head. But there’s awesome books, awesome resources outside of me that can speak more to these different areas. And I love it that you guys have found that.

Thank you guys both for what you’ve offered for us today and our listeners. The advice that you’ve shared, and all that you’re doing in terms of this area, this evolving area of trying to manage these efforts, these initiatives to make new things and to make better things happen.

PETER GREEN: It’s our pleasure. We appreciate the work that you’re doing on the Manage This podcast. Love the show, and are really excited to be on it.

Closing

WENDY GROUNDS: That’s it for us here on Manage This. Thank you for joining us today. You can visit us at Velociteach.com, where you can subscribe to this podcast and see a complete transcript of the show.

You’ve just earned your free PDUs by listening to this podcast. To claim them, go to Velociteach.com, choose Manage This Podcast from the top of the page, click the button that says Claim PDUs, and click through the steps. Until next time, keep calm and Manage This.