All day, every day you’re presented with information, ideas, and nuggets of inspiration.

That enlightening article you read while sipping (okay, chugging) your morning coffee. That podcast episode you listened to at the gym. That resonant quote printed on your coffee cup.

Every single day is an avalanche of input (and you probably have the fatigue and eye strain to prove it). And while you might jot down the occasional hard-hitting factoid into a random note on your phone, you probably don’t have a polished system to store that information—let alone connect the dots between disparate facts, form new ideas, and retain what you learn.

The Zettelkasten method is an approach to notetaking that turns information into something way more powerful: knowledge.

Who invented the Zettelkasten method?

The Zettelkasten method was invented by Niklas Luhmann, a German sociologist, in the 1950s. Luhmann was a prolific writer, publishing over 50 books and hundreds of academic articles during his career. But Luhmann didn’t credit his own superior intelligence for his productivity—he credited his notetaking system.

What is the Zettelkasten method?

Zettelkasten is a German word that loosely translates to “note box” or “slip box,” both fitting names for Luhmann’s simple system. He used a crate or a box (a kasten) to store an ever-growing collection of index cards (zettels).

Each index card contained a single note or idea, with a few other rules that Luhmann always followed when jotting things down:

- Write the note in your own words, rather than copying or using direct quotes

- Write the note as if you’re writing it for someone else so you include enough context

- Include the source of the information so you can always find it again

Luhmann also developed a couple of different types of notes to log information:

- Fleeting notes: These are the random thoughts and epiphanies that pop into your own head throughout the day.

- Literature notes: These are notes taken when reviewing and consuming content, whether it’s an article, book, presentation, podcast, or any other resource.

At the end of each day, he’d review his fleeting and literature notes, decide which tidbits were worth keeping, and then translate them into permanent notes—the slips that he would “officially” file into his kasten.

Using Zettelkasten for less chaos and more connections

Sounds simple enough and maybe not all that magical, right? But the real power of the Zettelkasten method comes from its ability to form connections between seemingly discordant pieces of information—to go beyond committing random factoids and details to memory to see the whole picture.

Luhmann did that with a numbering system. He didn’t attempt to categorize and file notes based on topic (doing so would limit his understanding to a set discipline, after all) and instead assigned each card a fixed number.

As he collected more notes, he was able to “link” thoughts together by expanding on the numbering system. Card 1/1 contained the original note or idea. Card 1/1a built on the original note. Card 1/1b did too. Card 1/1b1 referred to an idea from card 1/1b and so on.

That super analog numbering system might make your eyes glaze over now, but you don’t have to do it exactly this way (we’ll dig into this a little later). Basically, think of it as linking before linking was a thing. What Luhmann did was essentially build his own Wikipedia—a reference database that could efficiently direct him to other relevant information.

Okay, so how do you do the Zettelkasten method?

The Zettelkasten method was developed in the 1950s, but things have changed a lot since then. Most of us aren’t going to thumb through drawers full of index cards when we need to recall a relevant nugget of wisdom.

So how exactly does the Zettelkasten method work in today’s digital age? The basic principles still hold true even if you aren’t using pen and paper. Here’s a quick and simple overview of how to apply the Zettelkasten method for your own (or your team’s) knowledge management.

1. Choose your method

You don’t have to go the index card route (no shade to Luhmann, of course), but you do need to figure out exactly what you want to use to create your own Zettelkasten.

Do you want to create a huge spreadsheet? Use a Trello board? Set up a running Confluence document? You don’t need to look for a fancy Zettelkasten method app—there are plenty of digital solutions you’re already using that could do the trick for storing and linking your ideas.

2. Start writing notes on the go

Remember, creating a Zettelkasten isn’t about designating specific topics, folders, or other limiting constraints. This isn’t your typical “here’s the folder for blog post ideas” and “here’s where we’ll collect website inspiration” approach.

Instead, stay open and collect information as it piques your interest. That’s it. When you find something, write it down—in your own words and with the original source, of course.

Hypothes.is, a company funded by Atlassian Ventures, offers a unique way to capture notes digitally. Everyone has been on a website and thought, “Ooh, I wish I could share this info with my team!” Whether it’s a screenshot in chat, or copy and pasting, the information you grab from this site ends up outside of any context and you forget where you put it later. Hypothes.is allows you to annotate information you see on a website, and then keep and share that information within a Confluence doc or Trello card.

So for example, let’s say you’re doing market research and you see another company’s website displaying information in a really cool way that easily demos their product. You take a note within the Hypothes.is browser extension, and then embed your notes on a related Trello card.

3. Review your notes

If you recall from our original explainer, any inputs will be logged as two different types of notes: fleeting notes and literature notes. Then it’s up to you to review those, transfer them to permanent notes, and add them to your Zettelkasten.

Keep in mind that your permanent note will be more complete and should include a(n):

- Thorough explanation of a single piece of information or idea: Aim to include somewhere in the range of three to five sentences. That’s enough to provide context, but not so long that it’s cumbersome.

- Original source: Whether you’re listing a podcast name and episode number or including an actual link back to the origin, it’s crucial that you jot down where you initially found that nugget. You might want to revisit it at some point and you don’t want to have to do detective work to do so.

- Unique identifier: Luhmann used his numbering system, but maybe that’s too complex or cryptic for you. You have creative license to come up with something that’s personalized and works best for you.

4. Create your identification system

Let’s talk a little more about coming up with an identifier, as this is the piece of the Zettelkasten method that can feel the most daunting or confusing.

Remember the reason that Luhmann used his numbering system in the first place: to connect pieces of information to each other so he could easily and efficiently find related ideas. That’s it. You want your system to help you do that same thing.

Ultimately, you need to think not about how you want to store the information, but how you’ll recall the information. That doesn’t have to involve a series of numbers and digits if that doesn’t mesh well with your brain. And it doesn’t require Zettelkasten software either. For example, you could use something like:

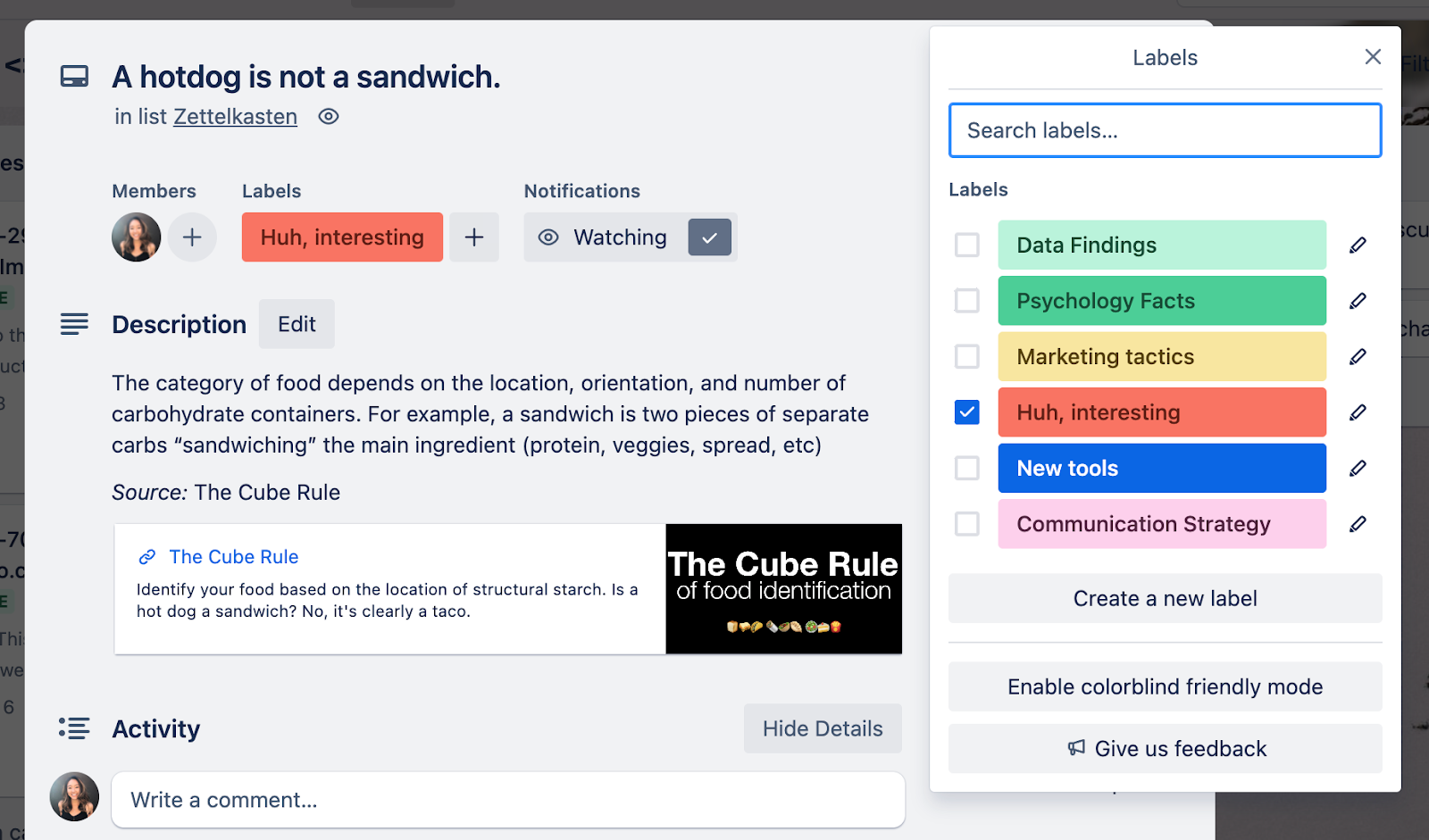

- Labels on a Trello board: Set up a Trello board as your Zettelkasten and create a card for each permanent note. You can assign a label (or multiple labels) to each card. You can also filter your Trello board by labels. So, if you only want to see information and ideas related to your “mindsets” label, you can quickly and easily do so.

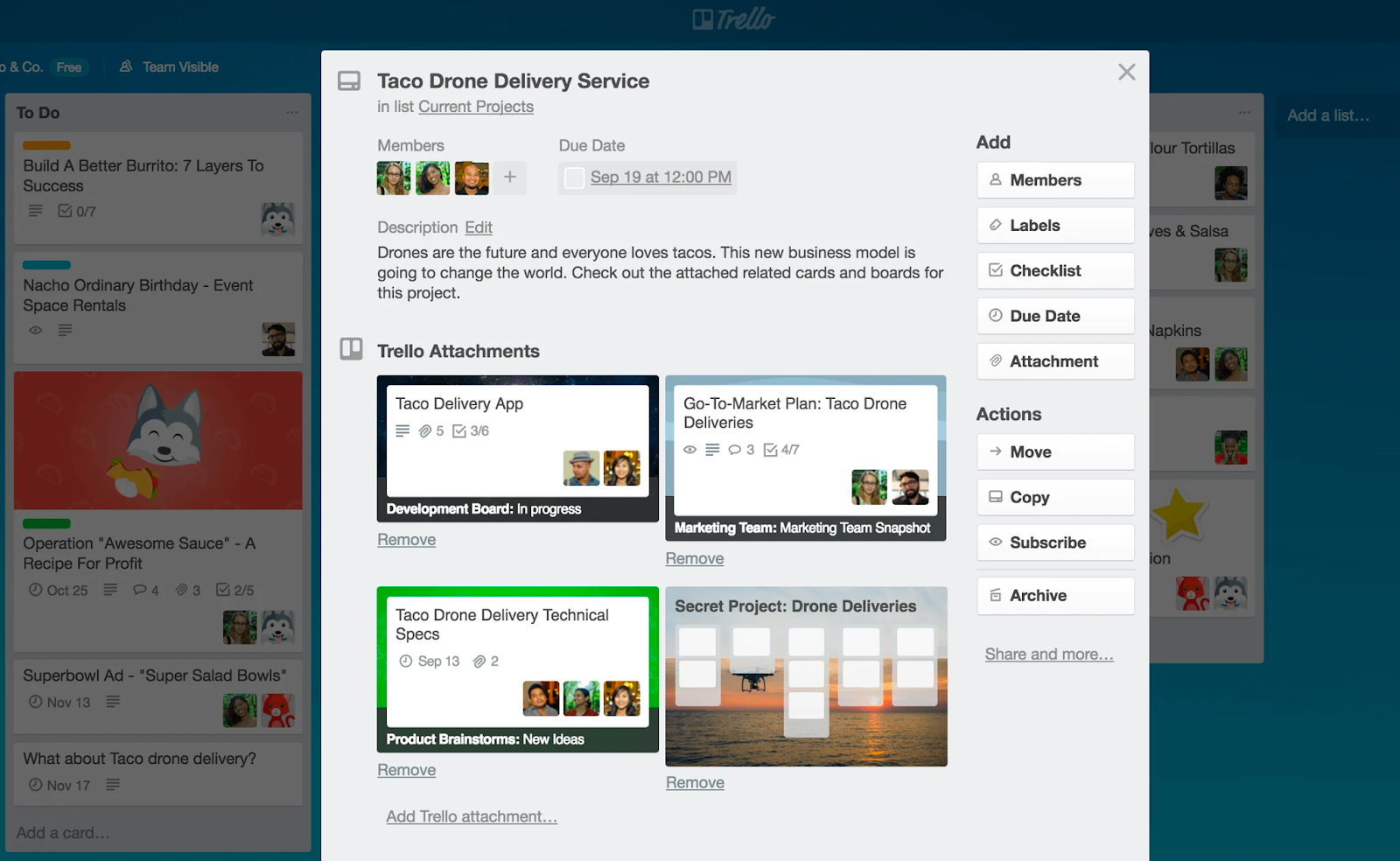

- Related Trello cards: On your Trello board, you can also attach other Trello boards or cards to each other. When you open up a specific card in your Zettelkasten, you’ll see related cards and boards in the “Trello attachments” section. This might become a little unwieldy as your Zettelkasten grows and you have more related content to link, but it can be a great way to get started.

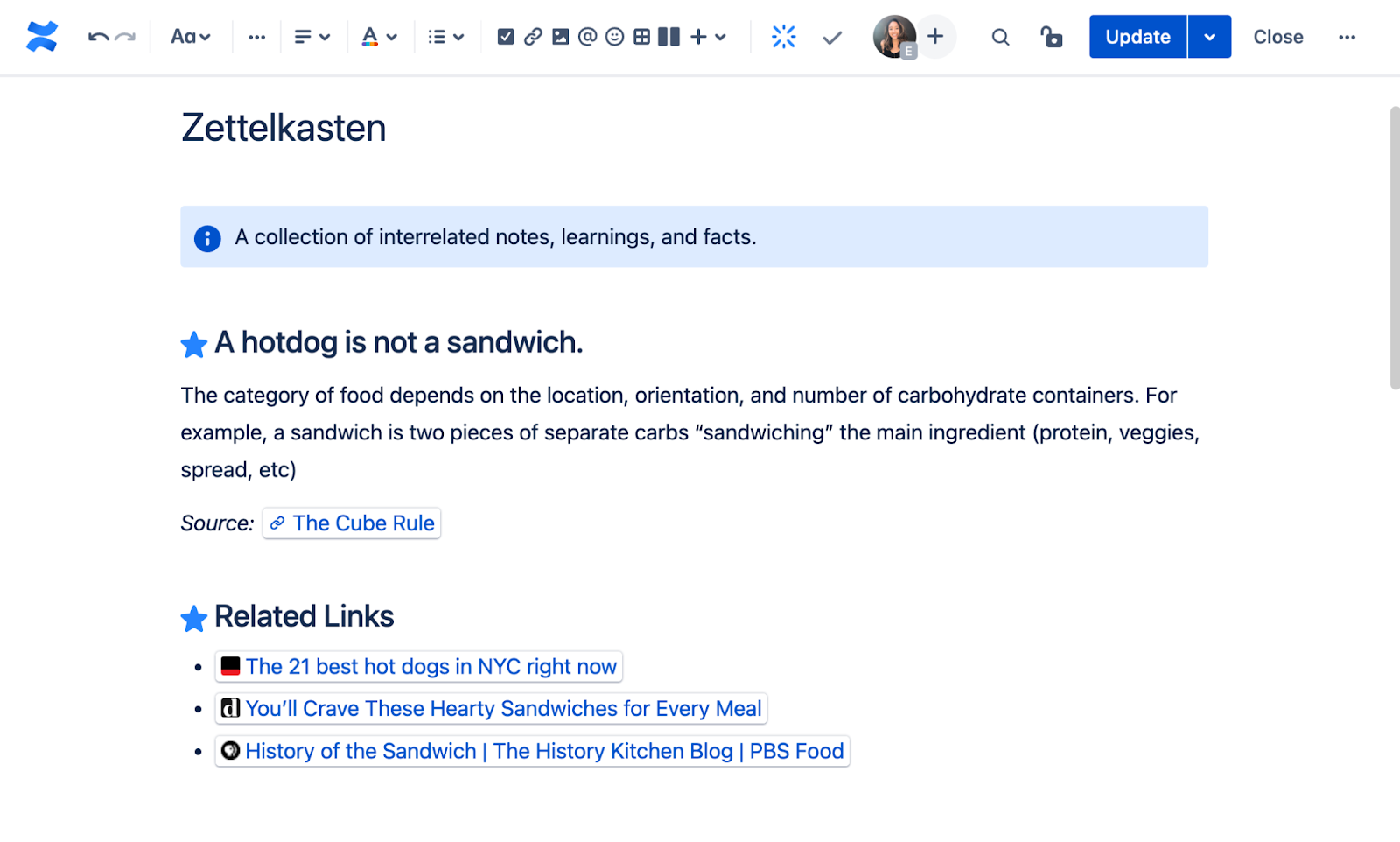

- Links in Confluence: If you’re using Confluence to build your Zettelkasten, links are what you’ll use to connect various ideas and factoids. Within Confluence, you can link to almost anything—external sites, Confluence pages, specific headings on a Confluence page, attachments, comments, Jira issues, and more. It’s an easy and intuitive way to build an interconnected web of information.

5. Continue taking notes

Your Zettelkasten isn’t something that you create once. Much like your own brain, it’s a living and constantly-evolving thing. So once you have the basics set up, commit to continuing to add to it.

As you create more permanent notes and link them to others, you’ll not only build a bigger Zettelkasten—you’ll build more knowledge.

What are the benefits of the Zettelkasten method of notetaking?

The Zettelkasten method might sound a little more involved than your current “system” (can we even call it a system?) of sticky notes and jumbled spreadsheets. And while creating your own Zettelkasten might have a little bit of a learning curve, it’s well worth it in exchange for the benefits it offers.

- Form strong connections: The thing that makes the Zettelkasten method different (and even a little unfamiliar) is that it’s interdisciplinary. It’s more about freeform notes and less about jamming them into specific categories, folders, or boxes. For example, you might learn about a specific psychological framework and create a note. With a lightbulb moment, that nugget could alter how you decide to market your newest product. Those are dots between psychology and marketing that you might not have connected when taking notes with a more rigid, hierarchical, or topic-oriented structure.

- Improve retention and recall: One of Luhmann’s rules was that you need to write a note in your own words. He wasn’t trying to give you a hand cramp—there’s a reason for this “extra” work. Think about it this way: You need to understand something well in order to explain it yourself. Also, research shows that going the extra step to write something down boosts our retention. And if your brain lets you down and draws a blank anyway? The numbering system helps you find what you’re looking for.

- Boost efficiency: Once your own Zettelkasten gets a little more built out, you’ll have your own personalized database of information. You won’t have to spend time scrolling through random documents, files, email threads, sticky notes, spreadsheets, and other resources. You can spend more time absorbing knowledge and less time managing it.

- Combat information overload: The Zettelkasten method mimics the way our brains work. Our brains don’t automatically categorize and store information for us, filing things away in designated folders to be recalled as needed. Intead, our brains are more like constantly running, interconnected logs of anything and everything—much like this approach to notetaking.

- Support knowledge sharing: A Zettelkasten is something that can be highly-personal and tailored to you, but it’s also something that you can do with your team. You’ll get important information out of everybody’s own brains (or inboxes) and into a centralized and systemized database where everybody can access it, learn it, and benefit from it.

Less information overload and more lightbulb moments

Every single day, you pick up on facts, ideas, experiences, and lessons. Ideally, those all come together and shape your understanding of not just a specific topic, but the whole world.

If you truly want to benefit from the avalanche of information around you, you need to retain those nuggets, connect them to each other, and form new ideas and conclusions for yourself.

Sound like more than your hard-working brain is capable of? Well, you might need to build your own second brain—and that’s exactly what the Zettelkasten method does.