PM Stories from the Front

War is hell, and not something any sane person plans for (outside of the government, that is). As the events of late have unfolded, the need for wartime planning of projects (military or not), has come to roost across most of Europe and beyond. Another black swan has landed, just a few years after the last.

Even non-military project managers are prepared for every eventuality, right? Our force majeure clauses in all risk assessments lay out what to do in the event of war, no? If not, wouldn’t the PMI PMBOK Guides™ definitively lay out the best practices and methodologies needed under these circumstances?

Well…actually no, they do not, nor do very few others outside of government and humanitarian agencies have procedures, techniques, or plans for the unfortunate event of an all-out war within a country or region. Yet during wartime, the work goes on and projects get completed (even for those who have never heard of a force majeure clause).

For this reason alone, I wanted to follow up on a past article, PM, CEM, and Covid-19: Reflections, since what is unfolding now could be thought of as the wings of an infamous mother-of-all bad geese: large regional conflict within the farmlands of Europe.

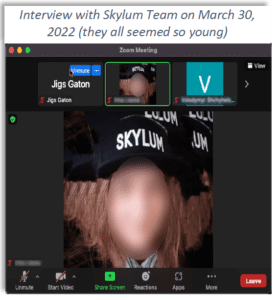

I’ll begin with an interview I had with a small software development company based in Kyiv. I was able to conduct a Zoom call directly with PMs who have been successfully managing projects during the first month of the war there. Then, I’ll follow that up with my own words, since much said during the interview was unspoken.

Other war stories will follow in this series, my editor permitting. I hope that these interviews, commentary, and “tips & techniques” will benefit any PM who finds themselves in the ultimate Black Swan situation, an all-out war or any other form of violent conflict.

First, a Little Background…

I had not meant to write any of this, but while vacationing in the jungles of Nepal (long needed after all this COVID stuff), I received an email from my favorite photo app developers, letting me know that since Ukraine was at war with Russia, software support might be slow. Huh? Slow? War with Russia? (I had my YouTube turned off.)

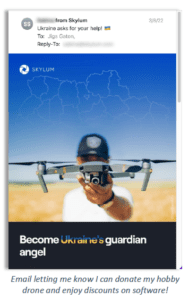

Since then, SKYLUM Software has put out two new updates for its most popular app NEO, and has continued to provide lightning-fast support as always… as if nothing at all was going on. I have also been getting a steady flow of marketing emails (as one does when you subscribe to an app), but now with notable differences. They included a donation request for commercial drones to be used for the war effort and discounts on add-ons, whereby the proceeds would be donated to humanitarian groups helping refugees leaving Kyiv. Not at all run of the mill offers from a run of the mill software house!

I had to figure out how they were doing it, as my first thought was: how is a software company still functioning whilst artillery shells rain down over their heads and their city is otherwise being invaded by another country? Just what PM methodology are they using to handle that? Is there a template in MS Project for war? Here is what I found out from the Skylum team. Names, faces, and details have omitted, for obvious reasons.

Interview with Skylum Software, Kyiv

Me. First, how are you? What is the status of your employees and your company at the moment?

PM #1. We are all doing okay, just fine. Everyone is safe. [said in a tone as if discussing a bad storm outside]

Me. Can you say a few words about how the company started? Where did you see the company headed before the war broke out?

PM #1. Yes, we started with our Luminar AIproducts a few years back, and after launching that we set to work on another, NEO, which we released in late 2021 as beta, and we are now updating the first version released this year.

Me. After war broke out?

PM #2. Yes.

Me. How many project managers (or people who manage workers) do you employ?

PM #1. Just three PMs, but we have both product managers and projectmanagers whose tasks are different, but connected. Our product managers work closely with our PMs.

Me. What PM model/method do you follow? Agile, Waterfall, hybrid? Are your PMs certified through PMI or another organization?

PM #2. None, and no.

[I felt the unspoken answer was, “we have our ways.”]

Me. Do you use Microsoft Project, by chance? Teams? Excel? Anything?

PM #2. No. No. No. No… it is proprietary.

[I so wanted to press on and find out more, but I didn’t.]

Me. What was your risk assessment for conflict disruptions five years ago, one year ago, and three months ago?

PM #1. We don’t really do those. There has been a risk of war like this for almost a decade now.

Me. So, no mitigations in place, even for Covid? PM #1. No.

Me. What advice, business-wise, do you have for managers of projects in conflict zones?

PM #3. Don’t ever get in this situation is the best advice that I can offer.

Me. You put out a plea for drones from your users. What was the response?

PM #1. Yes, we received over 100, and we are very thankful to our users for that.

[I wanted to send mine, but it’s in bits now after crashing during Covid times.)

Me. What would you like to say to western business leaders of companies like yours?

PM #1. To help Ukraine in the effort, and support the country in any way that you can.

Me. Thank you all so much for sharing your story, and may God watch over you all.

My Reaction to the Zoom…

In addition to my questions, the lead PM in charge of product design took the time to ask me questions, as a user of their apps. A user review, so to speak, they watched me go on about how great their products are while listening for an air raid siren or another signal of attack while. That blew me away! The calmness and professionalism throughout the entire meeting was remarkable. The word poise comes to mind, which this team has in droves.

This reminded me of times I’ve been under fire (with less poise, I must admit)—from being a Sarge during the Nam days to working on projects in the Congo, Pakistan, and Nepal during civil war and unrest. Yes, I worked within much larger structures than are found with your typical app developer, such as Skylum, but still, it’s worth comparing….

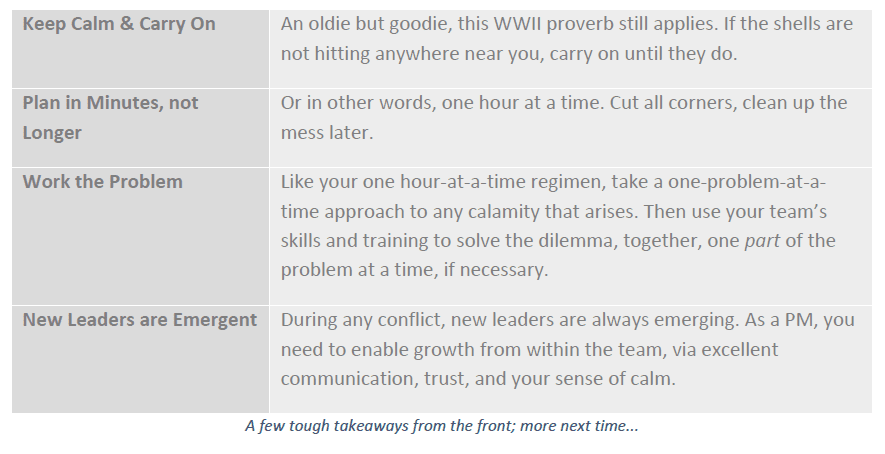

In larger organizations, there is a tendency to shift from normal chaos planning to some form of hyper-chaos planning. Those may or may not have the terms laid out in a risk matrix or other form of force-majeure document, but you get the idea. In some cases, the shop just shuts down until further notice (think headless chickens running). None of that was done in the case of Skylum. There, the day goes on, the work forwards to schedule, as if bombs are just part of the weather. If they aren’t falling near you, you are working. If something goes wrong, fix that, but stay focused on the end game.

In the military, there is a term for this method of working. You “work the problem,” and don’t let the problem work you. Simplistically, it sounds like a one-step-at-a-time series of actions, and in a way, it is, but with layers. Layers of act or react, observe, access, correct (if needed), and then move to the next issue.

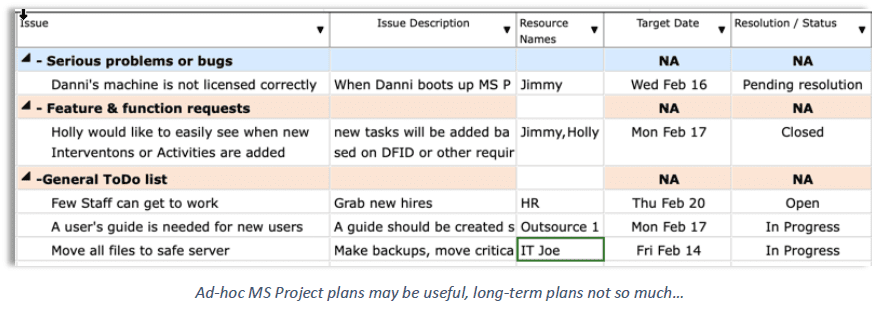

Microsoft Project might not be useful for planning in this way, nor may an Agile workflow be fast enough (as wartime compresses time), but your sheets and charts are useful nonetheless, even if only to remind the team of what has worked, and in what general direction they are going. During wartime, you need a compass, in whatever form you can find it. During my Zoom call with Skylum, I saw folks with a strong sense of no-nonsense direction. It was indicative of what we all see on the news these days from Ukraine: stories of people pitching in doing what they can, hardships or not, all pulling together as a unit, and then units of units.

Another example of this no-nonsense work-around for war is detailed in this interview by Ex-marine Mark Turner, involved right now with getting supplies and training to Ukrainian Territorial Defense brigades. He speaks of working the problem when trying to get across borders, through red tape, and other standard bureaucratic barriers, as his team delivers urgent medical supplies and front-line military training. (You can find out more about his organization here.) The point is that sometimes project managers may be required to adopt the military approach of tactical teamwork, instead of the traditional corporate one that we all know and love.

This military tactical team approach has been embraced at Skylum, as well as adopted by the entire Ukrainian state, where moral and national convictions are running high despite the circumstances. I’ve seen this ad hoc super-Agile approach work before on other projects. For example, in Nepal during their bitter civil war. Here are some takeaways I’ve found synced to all war zones:

Next Time…

In Part 2 of this series, I look forward to bringing you a few more stories from the frontlines (current and past), along with more specific correlations between tactical planning and normal project planning, for those times you may find yourself on a war footing. If you have some of your own stories that relate, feel free to send them to me or post in the comments below.

To donate funds to humanitarian-aid organizations in the Ukraine, go here.