The podcast by project managers for project managers. Selecting contractors and negotiating the terms of a major project is one of the most difficult aspects of project management. In this episode Ed Merrow sheds light on fairness in contracting relationships, for the relationships to be self-enforcing, and how not to unwittingly set your contractors up to fail.

Table of Contents

02:53 … Meet Ed

05:28 … Contract Strategies for Major Projects

06:59 … Hiring Contractors is Never Easy

07:55 … Key Principle #2

09:12 … #1 There is No Free Lunch

10:20 … TINSTAAFL

11:28 … #3 Complex Projects Need Simple Contracting Strategies

13:03 … Collaboration

15:07 … #4 Owners and Contractors are Different

17:44 … #5 Large Risk Transfers are More Illusion than Reality

19:25 … Importance of Scoping

21:29 … #6 Contractors have Shareholders

23:14 … Ren

25:29 … #7 Contracting Games are Rough Sport

27:05 … #8 Assigning a Risk to Someone Who Cannot Control that Risk is Foolish

29:07 … #9 All Contracts are Incentivized

33:20 … #10 Economize on The Need for Trust

36:40 … The Value of Prequalifying Contractors

40:13 … Getting the A-Team or the B-Team

42:48 … Get in Touch with Ed

44:02 … Closing

ED MERROW: …both owners and contractors play games. Contractors usually win those games. My advice is try to keep games out of your contracts. Try not to put in a bunch of complex provisions whereby you think that the contractor will “have skin in the game.” I want owners to remember that skin in the game is almost always owner skin.

WENDY GROUNDS: You’re listening to Manage This. This podcast is by project managers for project managers. My name is Wendy Grounds, and with me in the studio are Bill Yates and Danny Brewer. We love having you join us twice a month to be motivated and inspired by project stories, leadership lessons, as well as advice from industry experts from all around the world. We want to bring you some support as you navigate your projects.

If you like what you hear, please consider rating our show with five stars and leaving a brief review on our website or whichever podcast listening app you use. This helps us immensely in bringing the podcast to the attention of others. You can also claim free Professional Development Units from PMI by listening to this episode. Listen up at the end of the show, and we’ll tell you how to do that.

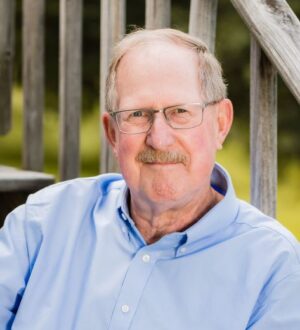

Today our guest is Ed Merrow. Ed is the founder, president, and CEO of Independent Project Analysis, the global industry leader in quantitative analysis and benchmarking of project management systems. Ed received his degrees from Dartmouth College and Princeton University; and he began his career as an assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. He followed that with 14 years as a research scientist at the RAND Corporation, where he directed the Energy Research Program. We’re talking to Ed particularly today about his most recent major research effort which is centered on the quantitative analysis of how contracting strategies and delivery systems shape project results. His new book is on this subject, and it’s titled “Contract Strategies for Major Projects.”

BILL YATES: In our conversation with Ed on procurement and contract strategies, Ed is going to share with us the key principles of contracting that all those involved with planning and executing major projects should know. Here are three things to listen out for on this episode. One, contractors may make convenient scapegoats, but they are rarely to blame for bad projects. Number two, we depend heavily on trust, yet trust is not a contracting strategy. And number three, contractors are almost always more skilled at playing those contracting games than those owners are.

WENDY GROUNDS: Hey, Ed. Welcome to Manage This. Thank you so much for joining us today.

ED MERROW: Well, thank you, Wendy. I’m glad to be here.

Meet Ed

WENDY GROUNDS: We are looking forward to getting into this topic. It’s not something that we’ve talked about before, and I believe you’re quite the expert and the right person that we should be talking to today. But before we go there, could you tell us a bit about your story, how you got into project management?

ED MERROW: It goes way back. After I left UCLA, where I was a professor, to go to the RAND Corporation, that’s really when I started my journey in projects. At RAND, I started the process of trying to understand why new technology projects overran so much, so often. That research ultimately led me to start Independent Project Analysis back in 1987; and we’ve been going strong ever since, really trying to understand at a first principles level the relationship between what owners, in particular owners, do on the front end of projects and what we get out in terms of project quality at the end. The contracting work that I’ve done is really very much part and parcel of that whole picture.

BILL YATES: This is going to be a powerful conversation for us to have for our project managers. This is an area that just scares the pants off project managers, excuse the expression. But when we get into procurement, and we get into contract types, many project managers just freeze and go, “Okay, this is scary for me. The more I can understand, the better, the more prepared I think I’ll be.” So this is a very valuable conversation we’ll have.

ED MERROW: It’s a very complex subject, that goes across economics, understanding markets, understanding competition, a lot of psychological factors associated with contracting. You know, I always describe project managers as a pretty hard-headed bunch in almost everything except contracting. When it comes to contracting, we often come to believe things that just plain aren’t true, in part because what we thought we learned about contracting in a particular project really was the wrong lesson. I wanted to step back and say, look, can we actually put some data around this issue so that we’re better guided as to what works and what doesn’t?

Contract Strategies for Major Projects

WENDY GROUNDS: Before we go into this a little further, I just want to talk about your book. You wrote “Contract Strategies for Major Projects.” Now, you have done a lot of research focusing on how contracting strategies and delivery systems shape project results, and you’ve shared those findings in this book. Can you describe the goals and the particular audience for your book?

ED MERROW: Well, my audience is primarily project managers and, to some extent, business sponsors of projects. Sometimes my audience will be procurement. Sometimes the audience is the legal side of projects, both on the owner and the contractor side. One of my hopes in writing the book is not only to shed some empirical light on the subject, but also to try to bring some sense of we need in our contracting relationships to be fair, and we need for the relationships to be self-enforcing, which is to say that the best contract in the world is the one that you sign, put in your lower left-hand drawer, and never see again. That’s the perfect contract. But when things don’t go perfectly, I want that contract to help us sort things out, rather than make things more difficult.

Hiring Contractors is Never Easy

BILL YATES: One of the things Ed that we wanted to bring to you, just thinking of some of the great quotes you had in your book, hiring contractors is never easy. And quite frankly, this is an area of great concern for project managers; you know? It’s like, okay, we have a project that we need to have done. We’ve got to go outside of our organization and hire some contractors to complete the work. Or it could be the owner that’s going about that contracting and seeking those people out.

This quote really made me laugh in your book. You said, “The worst contractor ever was the one on the last project, and the best contractor ever will be the one on the next project.” I like that. I can relate to that. You know, I’m an optimist anyway. So I might look at it and go, “Man that was a terrible experience we had in this last project. That’ll never happen again. This is going to be totally different in this next project.”

Key Principle #2

ED MERROW: You see, I always tell owners, and sometimes it upsets them, I say, “Look, contractors do good projects well and bad projects poorly. You’ve got to understand that almost has to be the way it is.” And I say that because, if a contractor can’t do a well-put-together, well-front-end-loaded, really strong business case project well, he can’t do any project well. And the market very quickly eliminates those players. Point of fact, contractors will do good projects well. And when as owners you set them up to fail, they usually will. Plain and simple. And the fact that they’re easy to blame doesn’t really change anything.

WENDY GROUNDS: That was number two of your key principles of contracting. I just took a look, and I thought, “I’ve heard that before.” What we want to run through today, we’ve taken these from your book because we thought they were the most applicable to project managers. So you have the 10 key principles of contracting. And you warn your reader in Chapter One, you say, “If one pursues a contracting strategy that flouts one or more of these principles, it’s very likely trouble is ahead.”

#1 There is No Free Lunch

So we’d like to run through these. I’m going to start with number one, which you say, “There is no free lunch.” Can you tell us what that means?

ED MERROW: Sure. Contracting always involves some version of what’s called the principal-agent problem, which is to say that a contractor will never perfectly do what an owner wants. It’s simply inevitable, if only because communication is less than perfect. So you’ve got to understand as owners that your responsibility is to put the project in a position where you’re not terribly dependent on the contractors being extraordinarily competent. Anything beyond ordinary competence, I would argue, is simply lucky for you. There’s never a free lunch. That principal-agent problem is always at work. Get over it, accept it, and move on.

TINSTAAFL

BILL YATES: Ed, I had an economics professor, I can’t remember, freshman or sophomore year when I was at university, and his statement was TINSTAAFL, there is no such thing as a free lunch. And he taught us TINSTAAFL, and it was a recurring theme throughout the course on economic principles that, “Hey, everything has to be paid for. There’s no such thing as a free lunch.”

ED MERROW: It all has to be paid for. And if you transfer risk, for example, as an owner, don’t expect it to be free. That’s naive. It won’t be. It shouldn’t be.

BILL YATES: And I like that you used the word “transparency” on this first principle because it sets up the conversation knowing there is no such thing as a free lunch. Therefore, as an owner, if I’m asking the contracting company to do something that I see is going to take some time, it’s going to take some resources, I cannot expect that to be free. It’s either going to be charged upfront, or it’s going to be buried somewhere else. So let’s be transparent right from the start and set it up that way.

ED MERROW: Far healthier way to manage a contractual relationship.

#3 Complex Projects Need Simple Contracting Strategies

WENDY GROUNDS: So talking about transparency, complexity is the enemy of transparency. Our point number three is “Complex projects need simple contracting strategies.” Could you talk more about that?

ED MERROW: First, the thing that’s really interesting is, as projects get small and relatively straightforward, contracting and contract approach, contract strategy, becomes progressively less important. And that’s because as an owner on a simple project, it’s easy to see what contractors are doing. You can watch it day to day. As projects get large, as they get complex, the visibility of the contractor’s performance goes down. And by the way, it goes down for the contractors, as well. So everybody needs to understand that. So it becomes really important that the contract itself not further complicate things.

In particular, there’s some contract forms, some approaches to project delivery that are intrinsically quite complicated, quite complex. For example, integrated project delivery, which is popular in some sectors, really suffers on complex projects, especially complex industrial projects. It just simply is not a contract form that works very well.

Collaboration

BILL YATES: There was a recent conversation we had with a project manager taking on the Palace Theatre. That was Robert Israel. We had a great conversation with him. And they were talking about, even though that space in Manhattan is so expensive, the need, the importance of having all the contractors represented in the same room in that project office that they set up. They talked about that being a key strategy.

And I think it lends to these points that you’re making Ed. It was almost forced transparency. They were looking at the same reports. They were looking at all the different departments that were represented many times by direct contractors. And they were meeting in real-time just to evaluate how is the project going, where are we falling behind, how can we shift resources, how’s this going to impact the other contract teams. So that just reminds me of that, and it rings home with this.

ED MERROW: I think that’s important. Remember, most of managing projects is really about moving information quickly, smoothly, without anybody hoarding information for their own benefit, be it personal or organizational. If we can move the information faster, we get faster, better projects. That’s simply the way it goes. What we need to also remember, a collaborative spirit is not contract dependent. In other words, let’s take the most, people will say, zero-sum type of contract form, EPC lump sum. That is a fixed price for design-build. The fact is I’ve seen design-build contractors and owners collaborate seamlessly. So collaboration isn’t really dependent on the contract form. It’s dependent on mutual respect and the willingness to be cooperative.

#4 Owners and Contractors are Different

BILL YATES: That’s so true. And this brings me to the fourth principle, which I thought was such a key, too, “Owners and contractors are different.” You think through this mutual respect. They need to understand they’re coming from a different perspective. They have different motivations. Owners have a certain set of motivations. They’re hoping to build an asset or build some additional value into their company through this product offering or service that the project will bring about. The contractors that they’re trusting and using and selecting, they’re looking at it through a different lens; right? They’re looking at billable hours. They’re looking at profitability. And they’re looking at resource utilization. Talk a bit about that because I think it’s a fallacy for us to think we’re all motivated by the same thing.

ED MERROW: Well I think it’s really important to understand that owners and contractors are very, very different kinds of economic entities. Owners make money by making products for sale with their assets. That means that most industrial owners are asset heavy. That means they have very robust balance sheets. And most contractors are precisely the opposite. Contractors are professional services firms, they’re not capitalized. They have those thin balance sheets.

And the way I try to bring it home, as I said, look, when you’re thinking about transferring risk, you need to understand that the first principle of how risk-averse you are is a function of your wealth to the size of the bet. This is why, if I ask you to flip a quarter for a dollar, most everybody says, “Sure, I’ll do it.” And if I say, “Okay, how about 10 million?” “No, I don’t think so. Thank you very much for the opportunity to be bankrupt.” Okay, and that’s because that second bet, which by the way has exactly the same expected value, that second bet has a huge downside.

Well, the trouble is that the contractors can’t afford those big bets. If you ask them to take them, they need to price them way up relative to what you as an owner might think is reasonable. That’s really important in understanding that, when it comes to carrying risk, we’re dealing with two very different types of economic entities.

#5 Large Risk Transfers are More Illusion than Reality

WENDY GROUNDS: Yeah, that leads perfectly into number five, where you say “Large risk transfers from owners to contractors are more illusion than reality.” If you think about it, most of the risk or all of the risk is really going to end up in the owner’s lap; isn’t it?

ED MERROW: At the end of the day, that’s right. That’s exactly where it ends up. And every owner knows that, even though they frequently behave as if they didn’t. On the owner’s side, we have an asset that we will have to live with for better, for worse, for a generation or two. Contractor is done. Okay? Soon as the project’s done, they’re out of town. It’s no longer their problem. So any difficulties, any quality problems, ultimately everything has to come back to the owner. If you as an owner understand that, then you’re far better positioned to make sure that you’re not trying to transfer your responsibilities to the contractor.

Let me put it this way. Transferring a risk in a contract from the owner to the contractor does not ensure that the risk will be managed. You simply have imagined that you have shifted the downside of that risk playing out. You may or may not have. Usually you haven’t. And remember, it has to be this way because contractors can’t carry heavy equity-type risk. They can’t do it.

Importance of Scoping

BILL YATES: Ed, this strikes to the importance of scoping a project and making sure that we’ve got the right requirements documented, and that owner and contractor are in sync in terms of what those requirements are, what they mean, how they’re documented. And it kind of goes to, if I’m an owner, and I’m really feeling like this is an area of larger risk, then I’m going to push more for a prototype, more for a proof of concept with those contractors.

I may say, look, I’m willing to pay extra money. I want you guys to build this twice, once very fast on a very small scale so we can play with it and see if it’s going to work, proof of concept. And then I feel like I’m stepping into the larger commitment with a little more sense that, okay, these guys can do this. These contractors can deliver this to the area of quality that I need.

ED MERROW: That is certainly true when we’re talking new technology. Okay? And remember, underpinning the design of every project is a voluminous basic data. And if the basic data are wrong, the design is wrong. The basic data responsibility are primarily an owner’s responsibility, not a contractor’s responsibility. And one needs to remember that, in law, there is something called the Spearin Doctrine, such that if you as the owner providing the basic technology and basic design, your mistakes really can’t be rectified by the contract. The Spearin Doctrine won’t let you off the hook. And while Spearin was a U.S. Supreme Court decision, it actually has been followed really throughout the world at this point. So in Europe all the way to Australia, the principles of the Spearin Doctrine are there, and you can’t skimp on the basic data.

#6 Contractors have Shareholders

BILL YATES: Ed, contractors have shareholders. Those shareholders are not the same of the owner. This kind of gets back to the prior principle that owners and contractors are different. Talk more about this idea of shareholders.

ED MERROW: Sometimes I think we, on the owner’s side, forget that the contractor managements do have fiduciary obligations to their shareholders. And those are not your shareholders. So the whole notion that you believe that the contractors should somehow contribute to your project with their financial resources is ridiculous. They have to be profitable. If they’re not profitable, they go away, just like any other economic entity in a capitalist society.

So we need to understand, and we need to appreciate, that they will need to make a profit. It’s not smart business – and most of the owners that I work with know this. It’s not smart business to try to stiff a contractor. That’s not what we’re looking for. What we are looking for is that the way in which the contractor will make a profit on the job is transparent, that it’s clear, that we know where that profit’s coming from and that there aren’t a set of other streams of profit that we can’t seek.

Ren Love’s Projects of the Past

WENDY GROUNDS: Taking a little break! Ren’s going to talk to us about the profession of project management!

REN LOVE: Ren Love here with a glimpse into Projects of the Past; where we take a look at historical projects through a modern lens. Today’s project feature is The Sydney Opera House in Australia – And if you haven’t heard of it – it’s right on the water in Sydney Harbour – and guys, I’m surprised there haven’t been more documentaries about the pure DRAMA that was the design and building of this place.

So the saga started in 1955 with an international design competition that called for proposals to build a new theater space in Sydney. There were around 230 entries, all of whom had to follow the same scope requirements.

All of those designs had to include two spaces: a large Opera Hall that could hold up to 3,000 people and a smaller one that would hold less than half of that. Both spaces had to be able to host lots of different types of performances, not just operas – but also things like concerts, lectures, and ballets.

After they chose the winning design, in 1955, the opera house was scheduled to be built in four phases – beginning in 1957 and ending in 1963. However, this project was full of issues like delays, rebuilds, design changes, and even the resignation of the main architect. It ended up being finished a whole decade later than planned. Not only that, but they blew the original budget of 7 million–the final cost came in at over 100 million dollars. That’s like 1000% percent over budget. In today’s dollars, that’s roughly a 1 billion dollar build.

So – could you call this project a success? Technically no. It was wildly over budget, behind schedule, absolutely plagued with scandal – But it’s currently valued at 2 Billion dollars and it’s one of the most iconic symbols of Australia itself. It was even in the running to be named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World – so, ultimately it was a success in its own way.

See ya next time for the next edition of Projects of the Past!

#7 Contracting Games are Rough Sport

WENDY GROUNDS: ED, “Contracting games are a rough sport.” That was your point number seven. And one other thing you said, I think, was contractors are usually more skilled at playing these contracting games.

ED MERROW: Their life depends on playing contracting games successfully. For owners, contracting games are strictly an amateur undertaking. So when it comes to various claimsmanship games, the contractors are going to be better at it than owners. They just have to be. This is why, when we try to put fancy incentives in place and so forth, generally those incentives can be gamed. Almost always they can be gamed.

There’s a wonderful series of articles by Jim Zack on claimsmanship. And I would encourage everybody to take a look at those. They’re absolutely brilliant. And both owners and contractors play games. Contractors usually win those games. My advice is try to keep games out of your contracts. Try not to put in a bunch of complex provisions whereby you think that the contractor will “have skin in the game.” I want owners to remember that skin in the game is almost always owner skin. It isn’t contractor skin. They don’t have the skin to actually get in the game.

#8 Assigning a Risk to Someone Who Cannot Control that Risk is Foolish

BILL YATES: That’s a great point. And again, this leads to number eight. This was probably my favorite of the 10. “Assigning a risk to someone who cannot control that risk is foolish.” Talk more about that.

ED MERROW: It’s just a fool’s errand. I mean, and we do it, we do it all the time. So what we imagine is, if I put in the terms and conditions that you’re responsible for this risk, then QED, the risk is going to be managed. No, it isn’t. If the risk is not manageable by me, then you’ve just created an unmanaged risk. Congratulations. Was that smart? Well, no, of course it wasn’t.

So, I mean, when we think about contracting, one of the things that we need to remember, contracts are all about risk allocation and risk assignment. And above all else, you want ownership and management of a risk to be crystal clear in the contract. If it’s not, any shared risk is your risk. It isn’t mine, I can assure you. Okay? So no shared risk, only assigned risks, assigned on the basis of who’s in a better position to manage the risk.

So, for example, when it comes to field labor productivity risk, owners don’t have the chops, the knowledge to actually manage that risk. That needs to be managed by the contractors. It needs to be managed by the constructor. When it comes to risks that flow from the front end, that’s the owner’s domain, not the contractor’s. So we need to be clear about who manages what, and line up risk assignment according to who can manage it.

#9 All Contracts are Incentivized

WENDY GROUNDS: Your number nine was “All contracts are incentivized.” And one of the points was that years of research have taught that incentives really work the way that the owners think they’re going to work. What can you include in the contract, these terms that are going to influence both the behaviors of the owners and the contractors?

ED MERROW: Well, this is where we engage in a lot of magical thinking. Okay? This is where I really do think that some project managers imagine things that just plain can’t be true. First, remember, any contract has in its terms and conditions, and in its payment scheme, a set of basic incentives. So, for example, a lump sum design-build contract is, from the contractor’s perspective, perfectly cost-incentivized contract. Every dollar I save is a dollar more that I make, okay, or a dollar less loss that I take. But it’s perfectly cost-incentivized.

So then we, because we’re so smart, we will add a schedule incentive on top of it. And then we wonder, does it do any good? Well, no, of course it doesn’t. Why? Because the contract was already cost-incentivized. Adding a schedule incentive on top has no effect except, if there is extra float in the schedule, I’ll take it out and make money for taking it out. But I would have taken it out anyway because I will always float the schedule to the lowest cost. Why? Because it’s a cost-incentivized contract. So when you add incentives that work against the primary flow of the contract scheme itself, you’re swimming upstream against a heavy current. And it’s just simply not really going to have any effect. Almost always, those supplemental incentives can be gamed; okay?

And one of the things that happens, and it’s kind of funny if you think about it, if you as an owner really believe that the only way that my contractors will do a good job is if they have a pain/gain incentive in the contract, then first you basically are saying they’re not professionals. They have to be bribed to do their work; okay? But then, interestingly, you’ve also painted yourself into a corner because, if in the first three months of the job the project is now overrunning, what am I going to do? They don’t have any incentive to perform anymore, do they? I’ll need to re-baseline the incentive.

And so I have projects where the incentives were re-baselined five and six times. Well, those are really tough incentives; right? I mean, that’s really holding feet to the fire. Well, all of that is just a game. And it is premised on the contractors not being professionals. That’s fundamentally wrong. They are professionals. And when they’re treated with respect, gee, they tend to respond very much the same way as professionals do. Most every contractor, engineer, or construction manager, whatever, comes to work in the morning to do a good job. Not to say, “How can I screw this owner’s project up today?” If they’re accorded respect, if they’re listened to, they feel they’re very much part of the effort, they respond accordingly. So that’s really where collaboration occurs, not in the contract.

#10 Economize on the Need for Trust

BILL YATES: Ed, this 10th principle brings back the idea of transparency, and the principle is “Economize on the need for trust.” Talk to us about that.

ED MERROW: Sure. Any economist will tell you, if something’s really valuable, you don’t spend it frivolously; right? Well, same thing with trust. It’s not that I’m saying that trust is not good. I’m not even saying that trust isn’t necessary for good relationships with contractors. But designing a contractual approach that is predicated on trust is foolish; okay? In other words, the contract needs to be a contract that both sides want to adhere to. And they want to adhere to it because it’s self-enforcing. What do I mean by that? I mean, my hope as a contractor is that I will do my best, we’ll have a good project, and the owner will give me a leg up on the next project. If owners are not faithful to that basic work for good work, then that relationship is not self-enforcing.

And sometimes I challenge project managers, I say, “Look, you’ve put a cost incentive in place for this reimbursable or unit rate contract. What do you actually imagine that that’s going to do for you?” And do you do that when you are about to have an operation? So you say to your surgeon, “Hey, doc, you do a good job on this one, and I’ll put something extra in the kitty for you.” Well, that’s going to be a great relationship, I can tell it now.

Or sometimes I’ll say to a project manager, “Basically what you’re saying is, if I do a really good job evaluating your project, I’d be happy to do that if you give me a little something extra.” And that’s not a professional services relationship. That’s kind of a mutual bribery relationship. So that just doesn’t work. That’s the wrong way to look at the whole process.

On the other hand, contracts should be clear. Contracts should say what they mean and mean what they say, as my old friend Rawles Jones, the federal judge, used to say to me. So it’s really important that contracts be clear. The contract terms need to be enforced. And if they’re enforced, you need to be sure that a fair result will come out. At the end of the day, contracting does have to contain an element of basic fairness. I understand that fairness is in the eye of the beholder, but we really need to be clear that, if things are patently unfair, they will never work.

The Value of Prequalifying Contractors

WENDY GROUNDS: Ed, those points were excellent. One other thing that I’d like to ask you about is just about prequalification. You have a chapter in your book where you talk about the value of prequalifying contractors, potential contractors. So what are helpful selection criteria that you would recommend for the contractor selection process?

ED MERROW: Well, basically what I want owners to do when they prequalify is to first ask themselves, look, what do I really want? In other words, what am I looking for? Am I looking for a contractor who can do something quickly? I mean, what is it that are my objectives? Then what I want to do is I want to establish criteria that will ensure that the contractors who are in that pool to be selected have the necessary skills to deliver what I need.

Now, some of the things we always do, and some of the things I think we do almost pro forma. So we always ask about safety. Okay? It’s almost like a holy grail. We have to ask about safety, and of course we should. Frequently, we don’t ask about safety, I think, in ways that are very telling.

So I don’t think we always look at insurance premiums, for example, which is a really good indicator. And we don’t always look at safety on jobs like the one that we’re proposing to prequalify for. But we do. We usually look at financial stability of the contractor. But what we need to be doing, especially in those lump sum design-build situations, is look at current projects and how those are going. Because remember, a project in trouble will occupy that contractor’s management attention far more than our new project will.

Sometimes we don’t ask for things that we really need. So we need data transparency. We need to flow cost information in real time. We need to actually, on the owner’s side, if we’re really interested in digitalization, we need to be taking physical possession of the designs. I mean, all of these are just basic things, and frequently we don’t really talk about them in the prequalification process. I mean, even issues like cybersecurity are now increasingly important, where we don’t want our design leaking out on the dark web, being sold to the highest bidder. So there are a whole bunch of things that we need that we don’t really talk about in prequalification. I think we should.

And in particular, if there are particular terms and conditions that we need, we want to put in the contract, and we’re going to put in the contract, let’s talk about them upfront in prequalification. Let’s not wait and then have those discussions down the road, when in fact we’re holding up the project. When we prequalify, we get better projects; okay? Plain and simple.

Getting the A-Team or the B-Team

BILL YATES: That’s a great statement. Ed, I worked with utilities for the first half of my career, 18 or so years. And one of the common complaints I heard from project leaders or those who ended up owning a project was, you know, I feel like the contractors pulled the old bait-and-switch on me. We didn’t get the people assigned to the project that I thought we would, or we didn’t get enough of their time. They’d show up, you know, just enough so we could remember what their name was. But they didn’t provide the all-star team that we saw during the presentations or in the proposal. That’s one of those prequalifying things, too. Who am I going to get?

ED MERROW: Yeah, it is. It is. But, you know, look, I have to laugh in a way because I was once talking to the CEO of a contracting EPC firm, and he says, “Owners are always talking about the A team. I want the A team.” Okay? And he said, “I just wish they’d tell me who my A team is.” Contractors are, you know, look, basically made up of B teams, and just like all of us are in life. And the fact of the matter is there are some things that we need to look at with respect to the team. I’m much more interested in not is this the A team, but has this team worked together before? So does this team actually know the contractor systems?

And, you see, I can put some criteria, some requirements around that. I can say, for example, here is the minimum percentage of the team that must have been with you on at least one prior project, maybe two, so that they’re not actually pulled together off the street. The project team that you give me must have done at least one, preferably two projects similar to mine before this one, or I’m going to disqualify you when I get the bids in.

In other words, there are objective things that you can do. Simply kind of the touchy-feely, I really liked that group that we met, well, if you didn’t like them, that’s important information because it means that the contractor doesn’t even have one group that’s likable. But in no way, shape, or form should you expect that that will be what you’ll get. And furthermore, you’re not really looking for people who are great at giving presentations. You’re really looking for people who are really good at managing projects. Not always the same.

Get in Touch with Ed

WENDY GROUNDS: Ed lastly, if our audience wants to get in touch with you, if they have questions, or if they’d like to purchase your book, where’s the best place for them to go?

ED MERROW: Oh, just my email address, and that’s just emerrow@ipaglobal.com. And I’d be happy to respond.

BILL YATES: Well, this is really helpful. These 10 principles, it’s like it tells a story; right? You know, to Wendy’s point, in the book, you lay these out. They’re all interrelated. They’re all so closely related to establishing and understanding the proper relationship between owner and contractor, the right things to expect and the unrealistic things to expect from both parties, and the need for transparency. This information, this advice will be very helpful. It’ll give assurance to project managers.

It’s commonsense stuff. They can look at it and go, okay, at the simple level, I can take on these challenges and implement these in my project. If I want to go deeper, I’m going to go next level. I’m going to keep peeling that onion and go deeper and deeper into Ed’s advice. So thank you for laying this out the way you did and for those principles.

ED MERROW: Well, thank you very much, and I enjoyed the chance to talk to you.

Closing

WENDY GROUNDS: That’s it for us here on Manage This. Thank you for joining us today. You can visit us at Velociteach.com where you can subscribe to this podcast and see a complete transcript of the show. I have added the links to Ed Merrow’s website on the transcript, as well as a link to where you can find his book.

You just earned your free PDUs by listening to this podcast. To claim them, go to Velociteach.com, choose Manage This Podcast from the top of the page, click the button that says Claim PDUs, and click through the steps. Until next time, keep calm and Manage This.