The article is based on the webinar “Fighting Uncertainty in Organizations, Including Matrix Ones, to Achieve Excellent Reliability” with TOC experts Eli Schragenheim and Albert Ponsteen.

Eli Schragenheim is a respected expert in organizational improvement and strategy, celebrated for his deep knowledge of the Theory of Constraints (TOC). He’s made significant contributions to the Theory of Constraints International Certification Organization (TOCICO), helping it gain global recognition. Eli’s innovative approaches and insights continue inspiring professionals and organizations worldwide to achieve operational excellence.

Albert Ponsteen is a seasoned TOC expert, mentored by Eli Schragenheim. He earned his PhD in resource management, underlining his expertise. Albert is the co-founder of Epicflow, an AI-driven multi-project management system. Born from rigorous research, Epicflow stands as a testament to Albert’s commitment to delivering intelligent and innovative solutions in complex project landscapes.

This article explores managing uncertainty in organizations. Although the key ideas are generic, special emphasis is on multi-project environments. Drawing from Dr. Goldratt’s philosophy, it emphasizes knowing something but never everything. The authors spotlight overlooked “common and expected” uncertainties like equipment malfunctions and seasonal variations. These seemingly minor uncertainties can cumulatively impact performance and disrupt detailed planning. The “Domino Effect” describes how these uncertainties can combine and amplify challenges. The article advocates for adaptive strategies and the use of buffers as protective measures against unpredictable organizational challenges.

1. The Philosophy of Knowing and Not Knowing

Never Say ‘I Know’ and Never Say ‘I Don’t Know’: You always know something but never everything.

The principle of never saying “I know” or “I don’t know” comes from a nuanced understanding of the constant uncertainty we live in. The founder of TOC, Dr. Goldratt, emphasized the point of “never say I know” as a reminder to stay humble about our knowledge. However, he was equally insistent that we usually know something about the subject matter. This balance between acknowledging our limitations and recognizing our abilities is essential in navigating uncertainty. It helps us begin somewhere rather than getting paralyzed by what we don’t know.

“When Dr. Goldratt came to me and asked, ‘Eli, how long will it take you to develop a new feature’, I hesitated. I was well aware that part of my code was complex and any addition would be risky. My first inclination was not to give him a number. But Goldratt insisted, ‘At least you can tell me whether it’s closer to two hours or two years.’ That’s when it clicked for me. He didn’t need a precise number; he needed a sense of the time frame. So, I told him, ‘It will not be more than two weeks.’ And he replied, ‘OK, this is what I wanted to know’.”

Eli Schragenheim

This paradigm shifts our perspective on how to approach uncertainty. It equips us with the mindset to acknowledge that while complete knowledge is unattainable, we must not let our gaps in knowledge deter us from making decisions or taking actions. It is this very mindset that shapes our approach to tackling uncertainty in organizations.

Read more: “Never Say I Know” and the Limitations of our (Reasonable) Knowledge

2. Identifying the Huge Impact of Common and Expected Uncertainty

In the preceding section, we laid the groundwork for understanding the nature of common and expected uncertainty. Because these uncertainties are considered “part of the job,” there is a tendency to underestimate their impact. The mistake here is viewing them as isolated incidents rather than cumulative forces that can weigh heavily on the organization’s performance and planning. Here, we will dive deeper into understanding its mammoth impact on organizational planning and performance. Although the emphasis is on multi-project environments, the key ideas are generic.

The Incidents That Don’t Surprise Us

Often, these are the uncertainties that are most overlooked precisely because they are so familiar. These could range from employee turnover, equipment malfunctions, or even seasonal variations in sales for businesses.

“I was approached by a company to investigate why a very important project that should have taken one year actually took five years. Management clearly did not think this was ‘common and expected’ uncertainty; they would have tolerated it for maybe two years. But the professionals who executed the project considered it a huge success. They said, ‘In the U.S., they have been working on it already for more than 10 years, and they are not close to what we have achieved.’ This was enough for me to deduce the team had set a one-year plan, knowing it is excessively optimistic because they were concerned that if they had told it could take five, or even ten years, the project would never have started.”

Eli Schragenheim

The lesson is: when you ask for a clear one-number estimation, without defining the level of common and expected uncertainty, then you either might face big surprises or face frequent occurrences, where the project/mission finished exactly on time. The latter case actually means that the mission could have easily finished before the planned time. Both cases cause severe damage to the performance of the organization.

The Impracticability of Detailed Planning

Common and expected uncertainty often messes up the execution of a detailed plan, making the original plan to be almost useless after a relatively short time. The more complex the plan, the more vulnerable it is to disruption from these routine uncertainties. Adaptive planning becomes crucial here. While having a plan is essential, the ability to adapt and modify it in real time is invaluable. The problem is that the intended outcomes and commitments to the market might be negatively affected, harming the reputation of the organization. This section discusses the challenges of planning in an environment filled with common uncertainties and suggests more dynamic, adaptable approaches, which most of the time contribute to achieving the desired objectives.

For instance, suppose the output of the project requires five different inputs from five different teams. What is the probability that the project will finish on time? Any delay in any input would delay the whole project, no matter how early the other teams submitted their inputs. So, what date should you offer reliably?

The Domino Effect

One of the most underestimated aspects of common and expected uncertainty is how it can accumulate. An employee’s unexpected sick day may not seem that impactful alone. But combine that with a minor delay in raw material delivery and throw in a sudden but not surprising market fluctuation, and you have a perfect storm. This is the Domino Effect in action: individual uncertainties, seemingly manageable on their own, can combine to produce an outcome far worse than any of them could individually. The cascading impact can be particularly detrimental to delivery performance, disrupting schedules and damaging reputation.

The above example of the five teams (see the end of the previous section) demonstrates a typical situation where lateness of one task is not compensated by other tasks that are early. This is the “integration effect.” Another situation for possible domino effect is when the output of a task, while on-time, fails to deliver the planned quantity, thus the subsequent operation has only limited inputs to work on, creating a negative effect throughout the chain.

Parkinson’s law states that work expands to fill the time allotted for its completion. Practically it means that when a planned task is delayed due to uncertainty, the delay is not compensated by other tasks finishing early. This behavior of Parkinson’s law causes much of the Domino Effect in projects, on top of the two above situations that generates an accumulation of delays.

3. Including Protection Mechanisms, Like Buffers, Against Uncertainty

In the previous section, we highlighted the underappreciated role of common and expected uncertainties in project management. This chapter digs deeper into a powerful tool for mitigating their impact: buffers. Beyond just time, buffers can cover finances, manpower, and more.

Everyday Strategies to Counter Uncertainty

Just as project managers use buffers to navigate uncertainties, we employ similar tactics in our daily lives. These aren’t complex plans but simple, intuitive steps that serve as safety nets for the unexpected.

- Catching a Flight (Time Buffer). When you need to catch a flight, you usually aim to reach the airport well before the departure time. This accounts for potential traffic delays, long security lines, or other unforeseen events.

- Preparing Dinner (Resource & Quantity Buffer). When hosting a dinner, you might buy extra ingredients. This accounts for the possibility of some ingredients getting spoiled, the recipe requiring more than expected, or perhaps an unexpected guest arriving.

- Saving Money (Financial Buffer). Financial advisors often recommend keeping an emergency fund to cover sudden, unforeseen expenses like a broken appliance or medical emergency. This is different from saving money for investment purposes, which is about growing your financial resources over time. The emergency fund acts as an immediate financial buffer, providing peace of mind and stability in case of unexpected setbacks.

- Carrying an Umbrella (Risk Buffer). Even if the forecast suggests only a 10% chance of rain, you might carry an umbrella when heading out for the day, just in case.

- Keeping a Spare Tire (Risk & Resource Buffer). Most vehicles come with a spare tire. Even if you never expect a flat, it’s there as a buffer against that potential problem.

- Having Insurance (Risk Buffer). Be it health, car, or home insurance; the idea is to have a buffer against unexpected damage or health issues.

- Dressing in Layers (Flexibility Buffer). If you’re uncertain about the weather, you might dress in layers. This way, you can adapt to a warmer or colder environment by adding or removing clothing.

- Backup Power/Charger (Resource Buffer). Carrying a power bank when out for long hours ensures that even if your phone’s battery depletes faster than expected or if you use it more than usual, you won’t be left without a functioning device.

- Learning Additional Skills (Skill Buffer). People often upskill or learn things outside of their primary profession. This not only helps in personal growth but also acts as a buffer in changing job markets or if one decides on a career shift.

In short, these everyday buffers help us manage uncertainties and offer peace of mind, reinforcing that while we can’t foresee all events, we can prepare for many incidents.

Buffers Mean Planning Spare of What We Might Need

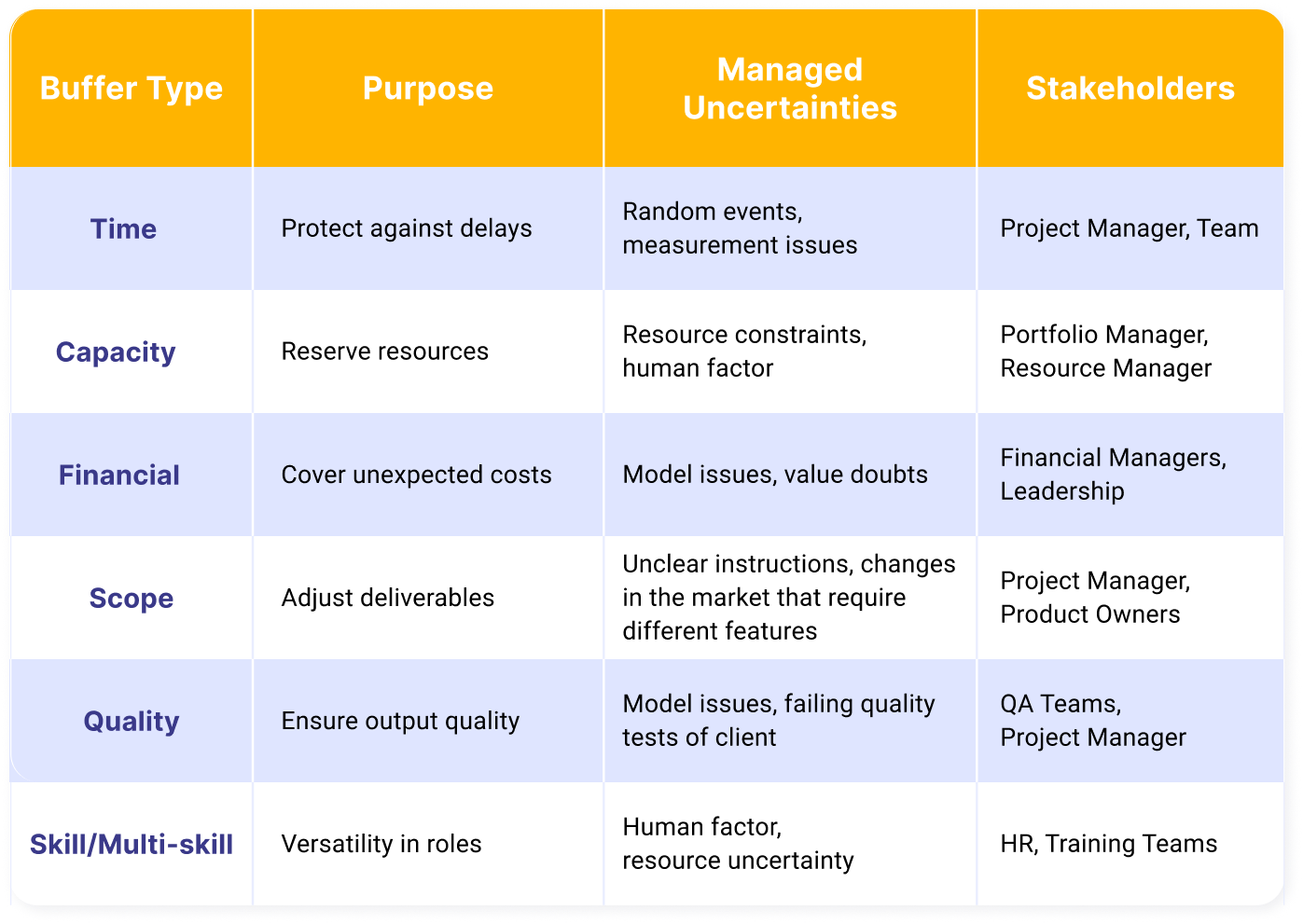

Buffers are vital tools in project management, used to mitigate various uncertainties. While time buffers are most common, there are several types to know, each targeting specific risks.

Buffer Types at a Glance

Buffers are surplus resources allocated to navigate inevitable uncertainties. For example, a project estimated at 100 work hours might include a 20-hour time buffer for contingencies like absences or technical issues.

“I remember being invited by the Olympic Committee of a country to consult on their planning for the Games. The date was fixed, the world would be watching, but what buffers did they have? You’ll be surprised: Their main buffer was a huge amount of money. Most of which could have been saved with better planning. Sometimes you need to ‘waste’ to create a buffer, but the trick is to waste wisely so as not to incur unnecessary costs.”

Eli Schragenheim

By strategically applying buffers—be it a financial buffer for a grand event like the Olympics or a time buffer for a smaller-scale project—managers can significantly enhance the project’s success rates and readiness for unforeseen issues. This real-world example underscores the importance of not only having buffers but also optimizing them to save resources.

The Stigma Against Buffers

Buffers are essential for managing uncertainties, yet they often meet resistance, especially in management circles. This skepticism arises from the belief that buffers are wasteful or overly cautious. When buffers are made visible, trust is crucial; without it, their presence can reinforce negative stereotypes, painting them as budget inflators rather than strategic tools. The key challenge is to reframe buffers as vital elements of proactive planning, dissolving resistance, and promoting a resilient approach to managing inevitable project uncertainties.

The Key New Insight: Include Visible Buffers in the Planning!

Making buffers visible in project plans fosters transparency and effectiveness. Unlike traditional hidden buffers, visible ones enhance project tracking and offer a measurable cushion for unexpected challenges. They also set realistic expectations by highlighting flexibility in planning. This visibility counters the stigma against buffers, framing them as strategic, rather than wasteful. In short, visible buffers improve accountability and project success.

Buffers Are Sometimes Partially Consumed

An important subset of these visible buffers is the partially consumed buffer. These buffers are dynamic and adaptable, offering the flexibility to make real-time adjustments. For example, if a project task initially includes a 20-hour time buffer and only 10 hours are needed, the remaining 10 hours can be reallocated or saved for future needs. Such flexibility not only allows for real-time optimization but also leads to more efficient resource management. The effective planning and use of these dynamic buffers are key for project success.

Planning visible buffers has to include the issue of where the buffers should be inserted. Protecting every single task within a project is useless. When we need to protect the completion of the project. Thinking about what could easily disrupt the safe completion and also ensure the quality of the outcome would lead us to note where the buffers are truly needed. TOC has fully developed methodologies for determining the right location of buffers in projects as well as in manufacturing.

Conclusion

Buffers serve as a crucial mechanism in the armor of project management against the unpredictability and uncertainties inherent in any project. While they are often misunderstood or misapplied, a nuanced and strategic approach to buffering can save both time and resources in the long run. Making buffers visible and understanding that they can be partially consumed allows for a more flexible, robust, and resilient project management approach.

4. Setting Priorities in the Execution Phase, Based on the Actual Consumption of the Buffers

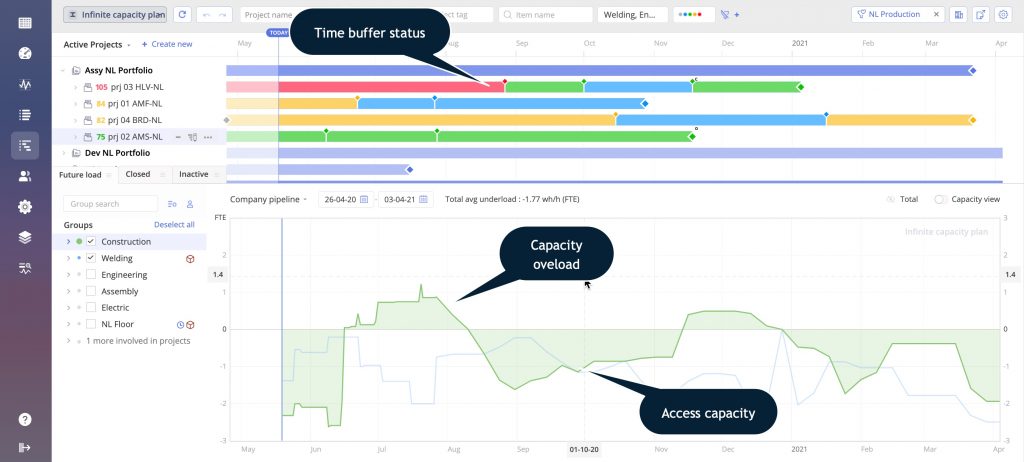

In this chapter, we’ll delve into the critical role of prioritization and buffer management during a project’s execution phase. We’ll emphasize the limitations of relying solely on time buffers and advocate for a real-time dual-buffer approach that monitors both time and capacity.

The Essential Role of a Unified Priority System

Navigating the complexities of multiple projects demands a unified priority system. This system serves as a single source of truth for decision-making and is informed by real-time buffer consumption, guiding efficient resource allocation.

In a multi-project landscape, a unified priority system is indispensable. It provides a stabilizing framework and helps avoid the pitfalls of striving for an elusive “optimal” solution, focusing instead on what’s practically achievable.

Read more: The TOC Contribution to Healthcare

Read more: Utilising Buffer Management to Manage Patient Flow

Monitoring the State of Many Buffers Leads to Identifying Situations Where the Whole Protection Scheme Might Crash

The effectiveness of buffers relies not just on their existence, but on ongoing monitoring and adjustment. As projects evolve, so should the buffers that safeguard them, meaning part of them is consumed by the incidental delays that have occurred so far. However, when implementing a buffer management system, a single focus on individual projects or processes can be short-sighted. A broader, more comprehensive outlook is necessary for effective risk mitigation and preventing potential cascading failures across the entire protective scheme. We need an early warning that the system might crash.

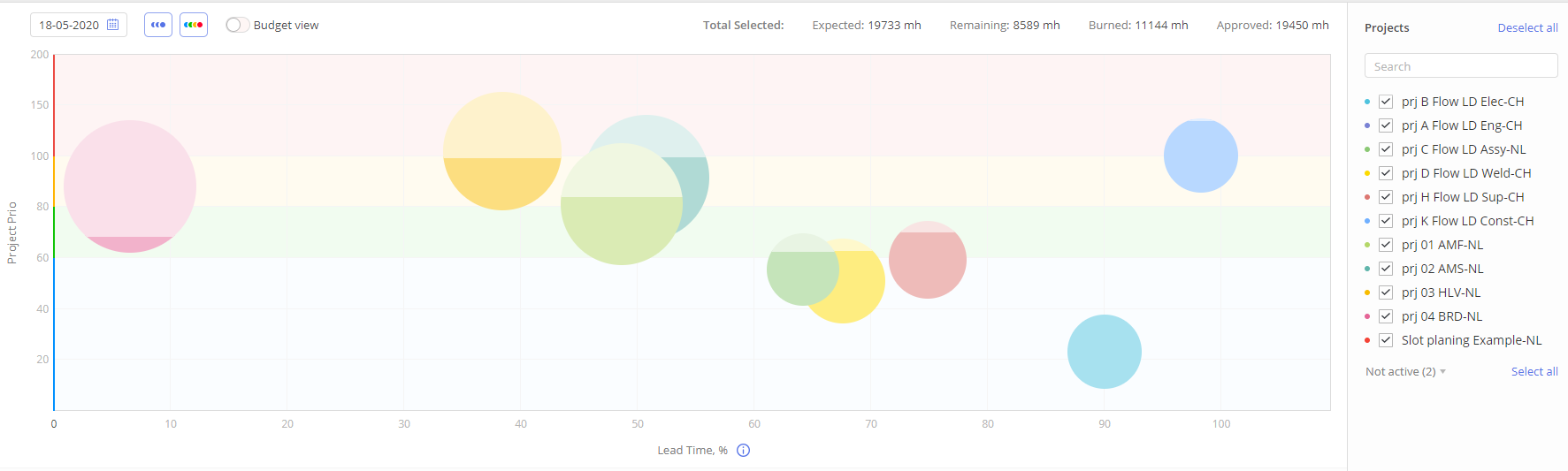

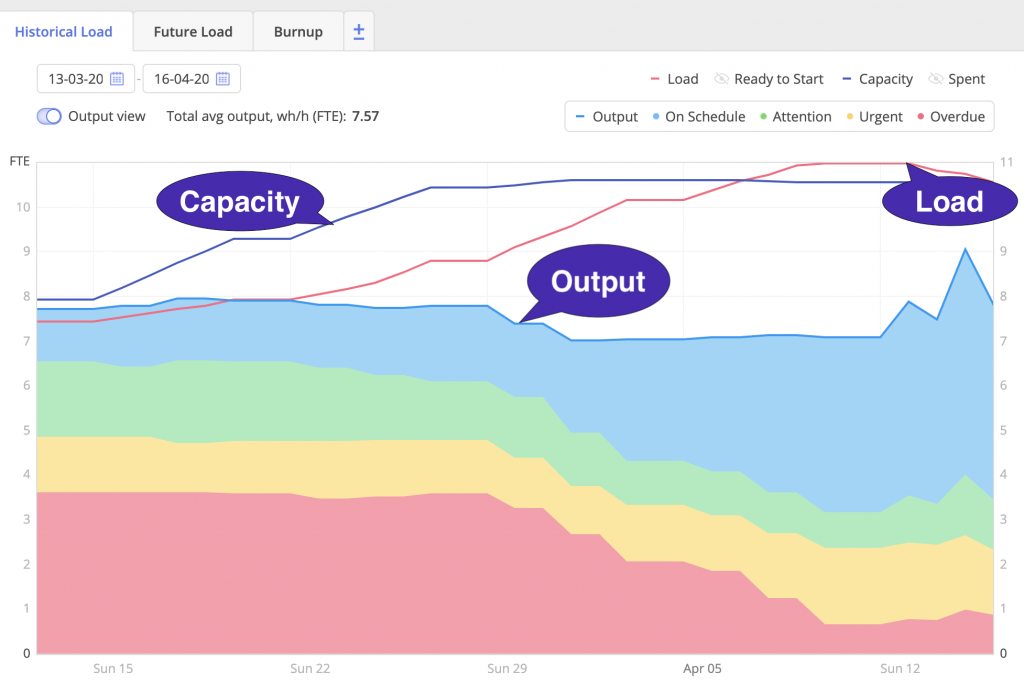

Monitoring the Buffers

In the context of managing uncertainties in multi-project environments, buffer monitoring is intricately linked with the “fever chart” of Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM). The fever chart graphically represents the consumption of project buffers against the completion of project tasks. By regularly monitoring the consumption of these buffers – whether they pertain to time, resources, or finances – organizations can derive real-time insights into the health and progress of their projects. This visual tool, when intersected with the buffer consumption rate, offers a clear picture of project performance. If the chart indicates a buffer being consumed too rapidly relative to task completion, it serves as a warning signal, indicating potential issues and enabling managers to proactively adjust strategies or allocate resources, thereby ensuring optimal project outcomes.

A modern version of a Fever Chart using infographics by Epicflow

The Hidden Risk: Relying Solely on Time Buffers

Time buffers, often represented through color-coded statuses, may be misleading indicators in a multi-project environment. While they effectively signal potential issues in individual projects, they fall short of capturing systemic risks. A few projects shifting from “green” to “red” may seem like isolated issues. However, when multiple projects turn “red,” it can expose the fragility of the entire system and trigger a cascade of failures. By this point, corrective action is usually too late to avoid widespread disruption.

The Missing Link: Capacity Buffers

Capacity issues, when overlooked, lead to significant obstacles in project management. If these issues are not addressed promptly, they result in what is called a “bottleneck” – a point of congestion where tasks accumulate, leading to delays. For instance, if a particular engineering team is stretched thin, all projects dependent on that team will experience delays. Since capacity isn’t project-specific but shared, a deficit impacts multiple projects.

Monitoring the level of access capacity provides the missing layer of protection. They alert management to shared critical resources that can derail multiple projects simultaneously. Neglecting to monitor capacity can leave the system vulnerable to unanticipated crashes, making the dual-buffer approach imperative for holistic project management.

Read more: Once in Red, Always in Red

Read more: The Critical Information Behind the Planned-Load

The Dual Buffer Strategy: A Comprehensive Approach

The most effective buffer management strategy incorporates both time and capacity buffers. This dual approach provides a nuanced, multi-dimensional view of project health, enabling proactive measures to avoid both individual project delays and systemic failures.

Dual buffer representation in Epicflow

Understanding History to Plan for the Future

Understanding the dynamics of capacity buffers to plan the future is incomplete without considering the historical performance of your teams. This data is not just a reflection but a predictive tool, embedding lessons from the past to enrich future planning strategies.

Consider an engineer scheduled for four 8-hour tasks in a 40-hour week. If only three tasks are consistently completed, a gap between planned and actual output becomes apparent. This recurring pattern isn’t a one-time anomaly but indicates a need for reassessment and adaptation in task estimations or effective capacity planning.

The incorporation of historical data ensures that future strategies are well-rounded, combining past performance trends and adaptive responses to uncertainties. This data serves not just as a record but a predictive tool, embedding past lessons to enhance future adaptability and resilience.

In cases where only three out of four planned tasks are consistently completed, it signifies an essential gap between planned capacity and actual output. Such insights lead to a reassessment of the benchmarks set for capacity. Informed by historical performance, adjustments can be made to align with actual output trends. This data-driven approach builds robustness and adaptability, ensuring that project plans are efficient and effective. It prepares teams for unforeseen challenges, enhancing the organization’s agility and responsiveness to change.

Historical performance measured in Epicflow

Conclusion

While time buffers are valuable tools, their utility is severely compromised if capacity buffers are ignored. A dual-buffer system that includes real-time monitoring of both time and capacity is essential for navigating the complexities of multi-project environments. This approach offers a comprehensive safety net, enhancing both individual project success and overall organizational resilience.

5. A More Generic Insight: We Should Estimate the Size of the Common and Expected Uncertainty as a Reasonable Range

The concept of “reasonableness” is subjective and varies from one situation to another. However, when it comes to forecasting, being “reasonable” requires us to rely on judgment informed by both data and experience. Too often, we see forecasts presented as a single number, creating an illusion of certainty that’s misleading. In truth, the term “reasonable” isn’t about aiming for pinpoint accuracy, but about grounding our expectations in reality.

Do Not Overprotect from Very Rare Incidents

Planning against highly improbable events, like your supplier being hit by a tsunami, may not be reasonable in most scenarios. Overpreparing for such outliers can tie up resources and lead to inefficiencies. The key is to prepare for what is most likely to happen. For example, if a supplier promises delivery in two months, a reasonable buffer might be planning for a three-month wait instead. This allows you to prepare for the “expected uncertainty” without spreading your resources too thin.

Use Risk Management Tools to Evaluate High Risks With Very Low Probability

For those black swan events that are highly improbable but catastrophic, other mechanisms like insurance or government protection schemes are more appropriate. These are separate from the day-to-day operational buffers and help shield against large-scale disruptions.

A major realization is: Don’t forecast ONE number -> always use a range!

Forecasts should always be expressed as a range rather than a single point. A range not only provides a more realistic picture but also allows for better planning and resource allocation.

Putting it All Together: The Need for a “Reasonable Range”

When it comes to decision-making, whether it’s forecasting sales for the next month or planning a project, we need to adopt the practice of using “reasonable ranges”. A range provides us with a cushion, offering protection without leading to resource wastage. This is critical, not just in supply chain decisions but in marketing, operations, and human resource management.

Budgets Should Reflect Realistic Buffers

In many organizations, budgets often have a narrow buffer, usually entitled as “reserve”, sometimes as little as 5%. This is usually insufficient for dealing with unexpected changes or opportunities. Budgets need to be more dynamic, with larger reserves that can be deployed when genuinely needed.

Forecasts as Targets: A Double-Edged Sword

Many organizations use forecasts as targets, which can lead to unintended consequences. For example, if you set a two-week target for a project, you can be almost certain it won’t be completed in less time, which is the essence of Parkinson’s law. People will often “use up” the allotted time, sometimes focusing on unnecessary details. Targets should be flexible, allowing for both over-performance and the unexpected.

Measurement Systems Need to Reflect Realistic Expectations

Just like university grading systems, where a score of 84% doesn’t really mean that the student did better than another student who got only 80%, and worse than one who scored 88%, we need measurement systems in the workplace that reflect broader categories. Instead of obsessing over small numerical differences, focus on what is “good enough”, what is “excellent”, and what is “unacceptable”.

Read more: Between Reasonable Doubt and Reasonable Range

Read more: Why should the Red-Zone be 1/3 of the buffer?

In Summary

When it comes to forecasting and planning, it’s essential to always think in terms of ranges rather than specific points. This provides a more flexible and realistic framework for decision-making and resource allocation. “Reasonable” doesn’t mean overly cautious; it means well-considered and flexible. As we become more experienced, our sense of what constitutes a “reasonable range” will become more accurate, allowing for more efficient and effective operations across all aspects of business.

References:

[1] “Never Say I Know” and the Limitations of our (Reasonable) Knowledge, Eli Schragenheim (2016).

[2] The TOC contribution to Healthcare, Eli Schragenheim (2016).

[3] Utilising buffer management to manage patient flow, by Roy Stratton & Alex Night (2009).

[5] Once in Red, Always in Red, Albert Ponsteen (2017).

[6] The Critical Information behind the Planned-Load, Eli Schragenheim (2016).

[7] Between Reasonable Doubt and Reasonable Range, Eli Schargenheim (2016).

[8] Why should the Red-Zone be 1/3 of the buffer?, Eli Schragenheim (2016).

[9] Webinar video: Fighting Uncertainty in Organizations, Including Matrix Ones, to Achieve Excellent Reliability, Eli Schragenheim & Albert Ponsteen (2023).